AMAZON FOUNDER JEFF BEZOS has never been seen in a top hat like the guy on the Monopoly board game, but, in every other way, he is a classic monopolist—the very model of a 21st century robber baron.

There’s at least one difference, however, between Bezos and robber barons of the past. While steel baron Andrew Carnegie became famous for building nearly 1,700 public libraries in small towns across the United States, Bezos has turned his wealth and power to strangling them.

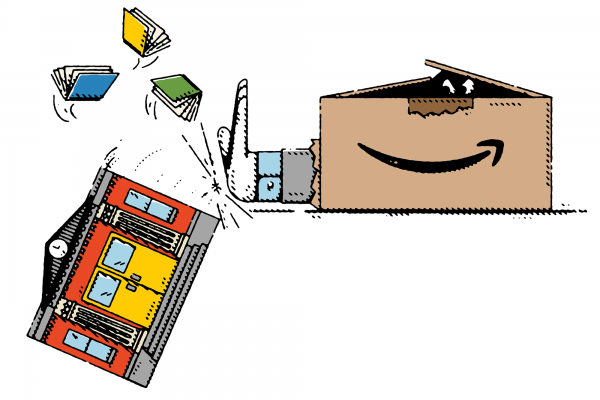

One mark of the monopolist has always been predatory pricing—selling an item at a loss to force a competitor out of business. As the first company to perfect an online ordering and delivery system, Amazon used that advantage to destroy its independent, brick-and-mortar retail competition. As rival online merchants emerged, Amazon systematically underpriced them until they shuttered or fled to the “shelter” of the Amazon Marketplace.

Another classic monopolizing strategy is vertical integration—controlling the supply chain from production to point of sale. When streaming video became the next big thing, Amazon didn’t simply start a streaming rental service, it went into the movie production business.

Read the Full Article