Rev. Moya Harris is an itinerant elder in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, currently serving as clergy staff at Metropolitan AME Church in Washington, D.C., most recently serving as executive minister. She currently is Sojourners’ senior director of programs. In this position, she uses her passion for justice and her love of scholarship to support those whose backs are against the wall.

Rev. Harris has served in various capacities for almost 20 years in ordained ministry and 30 years as a registered nurse. She is also a scholar, a wife, and a mother. She holds a bachelor’s in science degree in nursing from Towson State University and a master of divinity degree from Payne Theological Seminary. She is currently a doctoral student in the African American preaching and sacred rhetoric program at Christian Theological Seminary with foci in African rhetorical theory, Black prophetic preaching.

In the words of the late womanist theologian and ethicist Rev. Katie Geneva Cannon, Rev. Harris attempts to do the work her soul must have, marrying theory and praxis, scholarship, and service. She believes that justice and faith are inseparable and is quick to challenge violent theologies that attempt to oppress and marginalize. Even in these difficult times, she believes that God is still breaking through time and space, making all things new. She is passionate about scholarship, justice, hip-hop, and baseball. She can easily be found reading a book or writing a paper while listening to A Tribe Called Quest or The Roots while drinking a cup of coffee.

Speaking Topics

- Faith and justice

- Faith, health, and racial disparities

- Preaching and justice

- Homiletics and sacred rhetoric

- Hip hop, theology, and justice

- Black church and justice

- Black preaching and civil engagement

- Black and womanist liberation theologies

Speaking Format

- Open to virtual or in-person events

Posts By This Author

My Black Church Now Owns a Racist Logo

In June 2023, Metropolitan AME successfully sued the Proud Boys, winning a $2.8 million judgment through default judgement for trespassing and vandalizing our property. But because they have yet to pay, our church creatively sought to ensure payment by stripping the hate group of its trademark, meaning they can no longer sell merchandise to fund their hate — unless our church allows it. Any profits the Proud Boys earn from using the trademark must be paid to Metropolitan to help fulfill the multi-million-dollar default judgment.

This Election Is Critical. So Is Taking Time to Rest

Many of us have been working hard for months to shore up the freedom to vote for all citizens. We have knocked on doors, made calls to strangers, signed petitions, watched the news, created content, and equipped leaders on civic engagement strategies, hoping we will get the opportunity to rest after Election Day. For months, we have given our energy, sweat, and tears to ensure our communities are informed and equipped for this election. It seems like it will never end. But here’s the good part: We don’t have to wait until it’s over to get some rest.

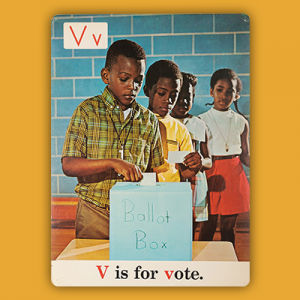

How I Resist the Stench of Jim Crow

Voter suppression has again taken hold. But I refuse to lose.

I PROUDLY SHARE the legacy of generations of people who fought to be respected as full citizens in America. I am the granddaughter of Mississippi sharecroppers. My parents picked cotton growing up, sometimes missing school to ensure the family could make ends meet. My parents left Mississippi in the late 1960s after college, having never voted. I know too well about voter suppression and the horrors of Jim Crow. The fundamental right to vote is close to my heart; it’s personal.

My generation was the first in my family born with full voting rights. I never thought the precious right to vote would be jeopardized in 2024. Yet, because the Supreme Court gutted the Voting Rights Act in 2013, the right of full and safe access to the ballot box is again impeded. Voter suppression has again taken hold as a tactic for dismantling democracy. The ghost of Jim Crow keeps on haunting.

Heaven Is a Hip-Hop Block Party

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the birth of hip-hop. From the rubble of gentrification and political abandonment in New York’s South Bronx, overlooked Black and brown kids used turntables and records to create new words and beats, movement and art. They built community and kinship, created meaning and culture, and developed self-worth in a world that hated them. “We were creating something that took up our time and made us feel good and brought us together,” Easy A.D., a member of Cold Crush Brothers, told oral historian Jonathan Abrams. “You have to imagine walking out your house every day and seeing abandoned cars burnt up, empty buildings, and you’re going to elementary school.”

The Spiritual Power of Lauryn Hill

If you listen to the album ‘The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill’ with an open heart and fresh ears, I believe that you will encounter God in new ways.

MUSIC IS MY safe space. When all hell is breaking out, I can put in my AirPods and turn on part of the soundtrack of my life and reset. The pandemic created a chronic hell that illuminated oppressive forces that have existed for centuries. Music became even more essential for my survival.

I am a Black clergywoman who is clear that “my emancipation doesn’t fit” many people’s equation. Let me say that another way: My authentic expression of self makes some people uncomfortable. My unapologetic expression of womanist Blackness often sheds light in the shadows of a corrupt world.

I won’t pretend that I have always felt free to be me. It took a pandemic to give space to be reminded by theologian and prophet Lauryn Hill that “deep in my heart, the answer, it was in me.” Hill’s lyrics and very existence compelled me to “[make] up my mind to define my own destiny.”

Some consider Hill to be one of the greatest lyricists of all time. An eight-time Grammy winner (with 19 nominations), she sings, raps, and acts. She is hip-hop royalty. In the ’90s, I wanted to be her. She wore the dopest locked hair style, had the most beautiful brown skin, and expressed her Blackness with boldness and class. She had, and still has, a lyrical flow that men and women couldn’t ignore. She was fly. (Translated as cool, sexy, smart, and stylish.)

Her industry-shaking debut solo album The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill, released in August 1998, will stand the test of time. Hill speaks truth in ways that penetrate the soul. I was a young mother when the album came out. She articulated things that only a Black woman could identify with. She spoke of the tension and beauty of having a child when society was telling her that motherhood and a career couldn’t coexist. She sang and rapped about self-respect, love gained, and love lost. This album is life. This album ministers. This album is sacred.

Women’s Needs Are Holy. Overturning Roe Ignores That

I have been ruminating on the significance of being a pro-choice Black clergywoman in a post-Roe United States. I understand how this may sound subversive despite the fact that two-thirds of American women disapprove of the Supreme Court’s decision last Friday to overturn Roe v. Wade. To some people, it’s incompatible that I could be a minister and support someone’s right to choose to have an abortion.

White Supremacists Defaced Our Church, But We Refuse to Lose

To be a Black woman in America and be relatively conscious, to paraphrase James Baldwin, is to be in a state of constant rage. Sweet holy songs don’t readily come to me. Christmas songs do not come to me. As a Black woman who happens to serve at a church that experienced white rage this past weekend when a group of demonstrators ripped down our Black Lives Matter banner and set it on fire, I am angry. And I’m tired.