IT WAS COLD — even for northwest Iowa in November. And I was late.

I thought I could make up time if I took the back way, a route I’d driven many times before. But the one-lane bridge across the Rock River was out and, judging by the abandoned construction site, it hadn’t been open for a while. I had moved away four years earlier and was a little behind on local traffic patterns.

To locals, the region surrounding the Big Sioux River drainage basin—stretching across parts of Iowa, Nebraska, South Dakota, and Minnesota—is known as “Siouxland.” To most Americans, this is flyover country.

I grew up in Siouxland, crisscrossing the region for family gatherings, 4-H horse shows, and trail rides, but I knew my time there was limited. Through TV, I learned about life in the big city and what the rest of the country thought of hicks, hillbillies, and hayseeds like me. I learned that to be successful, I had to leave. And so, like many of my classmates, I left as soon as I could.

I went to college in Minneapolis and pursued a career in media; after graduation I spent time in Los Angeles, New York, and Washington, D.C., working on shows such as Monday Night Football and Good Morning America.

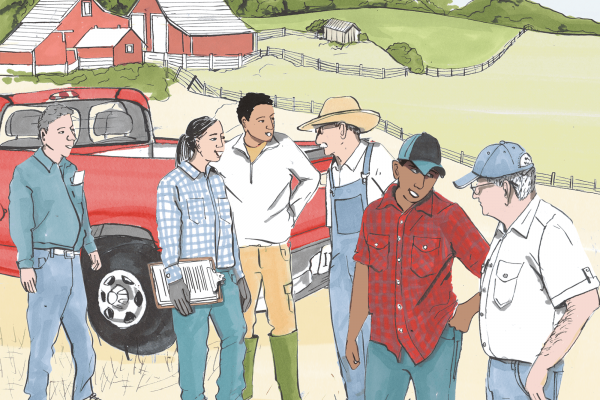

But on the morning of May 12, 2008, everything changed: Hundreds of federal agents from Immigration and Customs Enforcement raided an Iowa meatpacking plant, arresting 389 community members. At the time, I was a media producer for Sojourners, so I traveled to Iowa to cover the humanitarian response organized by Sister Mary McCauley, parish administrator of the local Catholic church.

Within hours of the raid, Sister McCauley had the entire community of 2,269 residents organized. When I interviewed her a few days later, the church was full of children still waiting to be reunited with their families. The church’s fellowship hall was filled with clothes, meals, and supplies for the children; community volunteers worked through legal paperwork on behalf of those detained. In a moment of complete chaos, community members rose to the challenge and stood together with their neighbors. It was at this point I realized the power of rural organizing. I was hooked.

Leveraging the gifts of the community

IN MARCH, AS the pandemic caused by the novel coronavirus erupted around the world, rural hospitals in the U.S. faced a particularly grim reality: Like hospitals across the nation, they faced a shortage of personal protective equipment such as N-95 masks and gowns. But unlike their urban and suburban counterparts, rural hospitals were already struggling. According to a 2017 study, 41 percent of rural hospitals operate at a loss, a result of decreasing Medicare reimbursements, more patients with underlying conditions, and fewer patients with private insurance. “We’re stretched thin as it is,” one hospital CEO told the Washington Post. “We’ll improvise and make it work however we can.”

As cases of COVID-19 skyrocketed, I thought about McCauley and all the organizers like her that I’ve met in the 12 years since the Postville immigration raid. Many of the best community organizers I know would never give themselves that title. They don’t work for a campaign or an organization. Often, they’re just everyday folks who believe their community is worth fighting for.

Read the Full Article