Stories matter. Our national stories convey what we value, what has shaped us, and where we have been. While it can be uncomfortable and even painful, telling the whole story about our history as a nation is both necessary and ultimately redemptive. However, as long as we take the path of deception, blindness, and amnesia, we will remain captive to the cruelty and inhumanity of our past. Yesterday I had the honor and privilege to visit the relatively new Legacy Museum and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Ala., joining with hundreds of other Christian clergy and leaders who were participating in this week’s annual Samuel DeWitt Proctor conference in Birmingham. The museum and memorial, both constructed by the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), left an indelible mark and served as a poignant reminder around the imperative to tell the whole, unvarnished story of America — because only the whole truth will set us free.

I had learned about plans to build the memorial back in December 2015 when I joined a group of faith leaders who spent three days with Bryan Stevenson and EJI. After the museum and memorial’s opening in April of last year, Sojourners published a number of moving articles about the groundbreaking significance of the memorial, which “is the nation’s first memorial dedicated to the legacy of enslaved black people, people terrorized by lynching, African Americans humiliated by segregation and Jim Crow, and people of color burdened with contemporary presumptions of guilt and police violence.” The memorial space is a jarring and stunning visual and physical manifestation of years of work by EJI to identify and memorialize more than 4,000 African-American men, women, and children who were lynched between 1877 and 1950, with their names engraved on 800 steel monuments representing each county in the United States where racial terror lynchings took place.

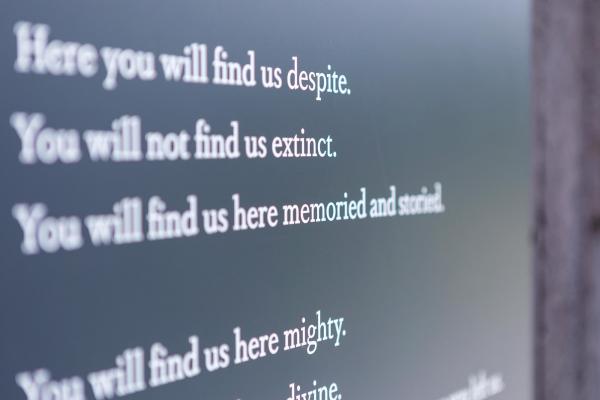

One of the initial plaques captures the purpose and mission of the memorial:

“At this memorial, we remember the thousands killed, the generations of black people terrorized, and the legacy of the suffering and injustice that haunts us still. We also remember the countless victims whose deaths were not recorded in news archives and cannot be documented, who are recognized solely in the mournful memories of those who loved them. We believe that telling the truth about the age of racial terror and reflecting together on this period and its legacy can lead to a more thoughtful and informed commitment to justice today. We hope this memorial will inspire individuals, communities, and this nation to claim our difficult history and commit to a just and peaceful future.”

During my time in Alabama, I got to hear a powerful sermon from Rev. Traci Blackmon, the Executive Minister for the United Church of Christ Justice and Witness Ministries, titled “We Have the Story” based on Joshua 4. She implored over a thousand of us gathered together that, just like Joshua, we must gather the stones of our sacred memory and tell the whole story of our struggle. Rev. Blackmon then recounted the story of Amadou Diallo, a West African immigrant who was wrongfully profiled by the four New York City Police officers and shot 19 times on the stairway of his house in 1999. In the aftermath of his senseless and tragic death, Amadou’s mother wrote a book to tell and reclaim her son’s story from the distorted narrative that had been told in the media. She wrote, for example, that he spoke seven languages and was a studious and hard-working immigrant seeking a better life. I was living in the city at the time, working for the New York City government through the Urban Fellows program. Amadou’s killing at the hands of police violence was a seminal moment in my own story by serving as a personal wake-up call to the dangers and realities of implicit bias and racialized policing. I was nearly fired that year for participating in a wave of protests during my off work hours that erupted across the city. Telling, or in this case yelling, the whole story is worth the risk.

The Legacy Museum takes you on a jarring journey by telling the stories of the 12 million people who were kidnapped and forcibly brought as slaves, the 9 million people who were terrorized by violence, including lynchings across the south, the 10 million people who were segregated under Jim Crow, and the 7 million people who today remain under control in the criminal justice system. The museum connects the dots between the seen and unseen ways in which racial repression has evolved throughout our nation’s history — from the shackles of slavery to indentured servitude post reconstruction and a reign of terror through lynchings to the stark injustices of Jim Crow segregation to the criminalization of black bodies through the war on crime to the era of mass incarceration and racialized policing that we are seemingly stuck in today. The museum tells the brutal truth about white supremacy in an uncensored and uncompromising way.

Just an hour and a half north in Birmingham you can find a more sanitized version of this history at the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute, which is located across the street from the 16th Street Baptist Church, the church where four girls were viciously killed in a bombing attack in 1963. While they cover much of the same history, I was struck after visiting each museum by how differently they tell the story. While still worth visiting, the Birmingham museum feels like stepping into a timemachine, as though the brutal history of slavery and Jim Crow segregation remain a vestige to a past that we must be aware of but that does not profoundly shape and confine our present. Some of the most moving parts of the the museum include where you can walk through a replica of segregated Birmingham, witness one of the Greyhound buses that was firebombed during the Freedom Rides, and witness the courage of civil rights leaders such as Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth, who the airport is now named after.

In contrast, in Montgomery the museum and memorial tells this story as one narrative arc that better connects the dots to our present, making a searing and convincing case that we can’t fully move forward unless we come to terms with our brutal past. At the Legacy Museum you can peer into a slave cell and watch as a slave woman pleads with you to help her find and reunite with her children. You can pick up a phone and listen to and watch a prison inmate tell their story, in one case of a woman who was raped by a correction officer while serving her prison sentence but whose baby was taken away from her after birth. You can watch a video of ex-convicts who tell their story of having survived heart-wrenching violence within St. Clair prison in Alabama, one of the most dangerous prisons in the U.S. The museum tells the whole story of how the criminal justice system remains the least impacted institution in American life by the civil rights movement and how the system’s endorsement of racially biased narratives has never been confronted.

As I left the memorial, I couldn’t help but wish that a replica could be built on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., so that far more Americans would be confronted with these stories. While I’m a big fan of the Museum of African-American History and Culture, it tells such a sweeping story that the specific history of racial terror can easily be overlooked and lost.

We can also learn from the experience of other nations that have grappled with histories of terror, including South Africa and Germany. I had the privilege of studying in South Africa for six months in 1997 at the height of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) and attended one of its public hearings. South Africa’s commitment to uncovering and unmasking its brutal past was incredibly moving and formative. The TRC gave opportunities for the perpetrators of apartheid to tell the truth about their crimes and receive public forgiveness. While the TRC fell far short when it came to delivering on promised reparations, it provided a remarkable opportunity for the country to confront the truth about its past and publicly lament for the atrocities that were committed.

The Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery was inspired in part by the way in which Germany has told the whole story of the atrocities committed under the Third Reich — through building hundreds of public memorials to the victims of the Holocaust. These memorials help to ensure that these atrocities are not forgotten and help to ingrain a deeper commitment to never allow them to happen again.

I left the memorial and museum wondering: What will be next? Will my 6- and 8-year-old son’s generation decide to construct memorials to the black men and women who were slain by racialized policing and police violence during the era in which they came of age?

I also felt even more convicted about the pernicious impact of the “Make America Great Again” mantra and slogan. America can never be great as long as we fail to confront our past — because core American ideals of equality, opportunity and dignity have been suffocated by our history of racial terror and suppression and still remain a major work in progress. I’m even more convinced that until we are capable of telling the whole story of our history we cannot be truly free and realize our full potential as a nation.

I feel indebted to the Equal Justice Initiative for having the courage and foresight to model how to tell the whole story. And I hope and pray that this can inspire us to better tell the whole story about other parts of our history — from the extermination and brutal treatment of Native Americans to the subjugation of women to violence and discrimination toward the LGBTQ community. A plaque near the end of the memorial captures this best when it reads:

“For the hanged and beaten. For the shot, drowned, and burned. For the tortured, tormented and terrorized. For those abandoned by the rule of law. We will remember. With hope because hopelessness is the enemy of justice. With courage because peace requires bravery. With persistence because justice is a constant struggle. With faith because we shall overcome.”

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!