I CAN THINK OF MANY MISTAKES I made before turning 18, including a couple that could have landed me in juvenile detention: fireworks in the suburbs, running from the cops, lying to the cops about running from the cops, and one or two others I’ll keep to myself because everyone I interviewed for this story insists on this: Nobody is the worst thing they have ever done.

If those words are true, Sara Kruzan will not always be the 16-year-old who shot her sex trafficker in the head right after he took her to another hotel room.

And that means Krys Shelley is not just the 17-year-old who used an unloaded gun to rob someone.

But back when Shelley stood trial as a teen, the judge only saw a criminal. Shelley still remembers what the judge said before delivering the 12-year sentence: “Good luck.” He studied Shelley closely. “You’ll do just fine in there.”

Shelley believes that the judge felt like Shelley fit the bill of a juvenile delinquent—black, tall, and masculine. At the time, Shelley identified as a tomboy (today, Shelley is gender nonconforming). From an early age, Shelley could grow a full facial beard because of an inborn hormone imbalance—a common symptom of polycystic ovarian syndrome.

But it’s less about what the courts saw in Shelley, and more about what they didn’t see: an honor-roll student with a steady job whose pastor came to the courtroom to offer support.

Shelley was sentenced during the ’90s, a time when crime among adults was going down, but crime among youth was spiking at never-before-seen rates. Americans were scared. “They were going around saying that we have a new species of child in America,” said criminal justice reform advocate Bryan Stevenson. “‘And these kids may look like kids, they may act like kids, they may sound like kids,’ they said, ‘but don’t be deceived. These are not children ... These are super-predators.’ And it didn’t matter whether you were a Democrat or a Republican. Everybody wanted to be tough on the super-predators.”

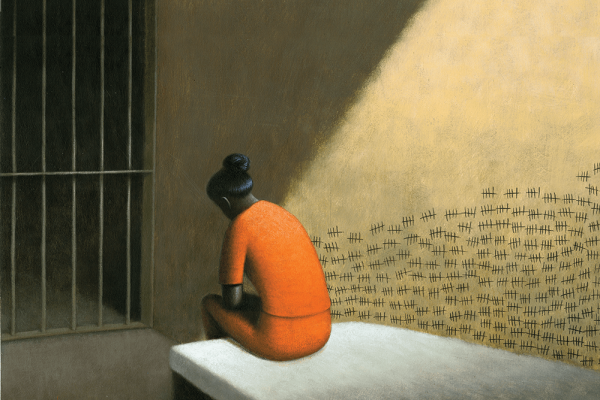

The concern over the rise in crime was legitimate, but the response—like so many “solutions” birthed in fear—was dangerously hasty. States all over the country implemented harsh mandatory minimums. California created the three strikes law, which gives a mandated term of at least 25 years to someone found guilty of committing a combination of a violent felony and two other convictions. Florida created the 10-20-Life law, commonly known by its unofficial slogan: “Use a gun, and you’re done.” In many states, juvenile offenders were not exempt from the severe sentences mandatory minimums prescribed. Today, there are more than 2,500 individuals who have been sentenced to life without the possibility of parole—for crimes they committed before age 18.

What the jury didn’t know

When Sara Kruzan was convicted of murder as a teenager, she became one of those individuals. But here’s what the judge never let her share in front of the jury: The man she shot, G.G. Howard, entered 11-year-old Kruzan’s life as a charming stranger riding a Mustang, offering her a double scoop of ice cream. He left her life with a bullet in the back of his head at a Dynasty Suites Motel. Somewhere in between those years, he raped her, groomed her for a life of prostitution, and became her pimp. Kruzan believes that her own mother was her first trafficker.

But there’s little room for context with mandatory minimums. Kruzan explained that the judge told her that Howard’s profession had nothing to do with her crime. He refused to let her attorney call expert witnesses to the stand who could speak to mental health concerns and child trafficking issues. Then he sentenced her to life in prison without possibility of parole.

Cases like Kruzan’s aren’t uncommon. In the past 10 years, advocates for criminal justice reform have identified a dark pattern: Almost every teenage girl in the juvenile detention system has endured family violence before entering the system.

A study of girls involved in Oregon’s juvenile justice system found that 93 percent had experienced sexual or physical abuse. Similarly, in a 2009 study of delinquent girls in South Carolina, 81 percent reported a history of sexual violence, and 42 percent reported dating violence. According to “The Sexual Abuse to Prison Pipeline,” a report produced by the Human Rights Project for Girls, the Georgetown Law Center on Poverty and Inequality, and the Ms. Foundation for Women, the “most common crimes for which girls are arrested—including running away, substance abuse, and truancy—are also the most common symptoms of abuse.”

I asked Kruzan what she wished had happened during her trial.

“If someone would’ve looked at me and asked me questions: ‘Why do you have cuts on your wrists? Why do you self-mutilate your legs or your stomach? Why is it that you can’t look at yourself in the mirror?’ Or even just, ‘Sara, why can’t you make eye contact?’ The signs were so loud and obvious. But they went ignored.”

Compassion isn’t efficient

Kruzan was asking for more time and nuance from her courtroom than our justice system often allows. She was asking the courtroom to see her as a human—one who hurt, feared, lashed out, and had some growing up to do. But grace is a pesky, time-consuming task. The mythical super-predator—who possesses some unshakable evil from birth—is a simpler story to understand than that of a flawed human with a troubled past.

“We have demonized and dehumanized the population that has committed offenses,” Javier Stauring, executive director of the nonprofit organization Healing Dialogue and Action, told Sojourners. “We make them monsters, and nobody wants to help a monster. It’s interesting how we can feel compassion for the young girl who is being sexually abused, who is being trafficked, up until the point that she acts out that pain. Once she falls into the category of inmate or criminal, she is no longer worthy of any kind of compassion.”

In the U.S. criminal justice system, grace and forgiveness become collateral damage to fear and efficiency. But while denying compassion is convenient, it isn’t an option for Christians. James Dold of the Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth explained it this way: “There is no such thing as a throw-away child.”

The Apostle Paul said it similarly: “I am convinced that nothing can ever separate us from God’s love. Neither death nor life, neither angels nor demons, neither our fears for today nor our worries about tomorrow—not even the powers of hell can separate us from God’s love.” Not even guns, not even violent acts of desperation, not even mandatory minimums.

Almost all the juvenile justice reform advocates I spoke with said the limitless grace of Christianity provides a needed critique to the senseless punitiveness of our criminal justice system. Over the past 20 years, social scientists have begun measuring the impact of Christian belief on a person’s view of the criminal justice system. In a 2005 study, criminologists James D. Unnever, Francis T. Cullen, and Brandon K. Applegate found that Christian belief is a key predictor for both punitive and rehabilitative preferences for the criminal justice system—and which end of the spectrum you fall on often hinges on your image of God.

According to the researchers, Christians who view God as angry and judgmental often hold punitive attitudes regarding criminal punishment and the death penalty. In contrast, those who imagine a gracious and loving God—“that is, those who take seriously the admonition to ‘turn the other cheek’—are less supportive of ‘get tough’ policies.”

And for Christians who cling to the latter view, this is an opportunity: While courtrooms are designed for efficiency, sacred spaces are designed for telling—and listening to—difficult stories. What if churches invited formerly incarcerated young women to share their stories behind the pulpit, passed the offering plate for an adolescent’s court fees, and preached about domestic and sexual violence—all the while preparing to walk alongside survivors?

Complex humans

For girls like Kruzan—survivors of violence who end up in juvenile detention—prison can be retraumatizing. Detainees are subject to routine strip searches every time they go outside or visit with a guest from the “free world.” After Kruzan turned 17, she was transferred to the county jail, where she endured the same naked searches, but with dogs sniffing around for contraband. “I understand these correctional officers are worried about their safety,” she explained, “but what about the mental and emotional safety of these kids? What I would want to ask the officers is, ‘Would you eat the fruit these kids are going to bear from being cultivated in your soil?’”

Currently, both Republican and Democratic lawmakers are seeking creative ways to tend to this soil. With women composing the fastest growing segment of the prison population—a 700 percent increase since 1980—the problem has simply become too big to ignore. Sen. Cory Booker has introduced a new bill, co-sponsored by Sens. Kamala Harris, Elizabeth Warren, and Richard Durbin, titled the Dignity for Incarcerated Women Act. If passed, the act would ensure that all federal penal facilities are staffed by people with trauma-informed training. The bill would also ban the practice of shackling women while they give birth and would provide inmates with menstrual supplies free of charge. Essentially, the law would be a statement that society should no longer render invisible young women who have committed crimes, and that we should see these offenders as complex humans worthy of dignity—and tampons—freely given. In August, the Department of Justice issued a memo instructing wardens at federal prisons to provide menstrual hygiene products for female inmates at no cost. The memo represents a huge step forward for women’s health in prisons, which would be further codified by the Dignity for Incarcerated Women Act.

Kruzan’s story is an example of what can happen once society starts to care about women who have committed offenses. In 2013, Human Rights Watch and juvenile justice reform groups helped raise enough attention about Kruzan’s case to get her a parole hearing. After 19 years behind bars, Kruzan walked free. Today, Sara Kruzan works with Javier Stauring at Healing Dialogue and Action, providing emotional support for teens who are imprisoned—in the same facility where she was once locked away.

Hurt people, healed people

Back in 2016, Ian Friedman was about to turn down the case of Bresha Meadows, a 14-year-old girl who shot her father in the head after enduring a lifetime of his abuse. But then he listened to what Bresha had to say.

“Mr. Ian, is my daddy dead?” she asked her prospective attorney. At the time, the news had only reported that Jonathan Meadows was taken to the hospital.

“Do you think it would be weird if I went to the funeral?” Meadows continued, after Friedman confirmed her father had died. “I love my daddy, but I hate him for what he did to me and my mom.”

Bresha Meadows originally faced a lifetime in prison, because the prosecution considered trying her as an adult for aggravated murder. But then the tweets, the prayers, and the complicated context of her case poured into the courtroom. In May, she accepted a plea deal to serve two more months in prison (in addition to the 10 she had already served) before receiving six months of mandatory inpatient mental health treatment. The ruling could have been a lot worse, but it could have been better, too. Her family had to come up with $70,000 to pay for that mental health treatment. But this is the real victory: After those six months, her record will be sealed and expunged, which may be the closest thing to a baptism the juvenile justice system has to offer.

In May, Meadows’ aunt, Martina Latessa, was asked how she felt about the proposed plea deal. She said she was optimistic for the first time in a while. “My main focus is Bresha’s well-being, Bresha’s life,” Latessa told Sojourners. “I want her to hold a productive life and be a contributing citizen and I want her—one day when she’s ready—to tell her story to other children.”

With the help of this mental health treatment, Latessa said she felt confident that Meadows could emerge from this mess as a forgiven and forgiving person with a powerful story to share. That certainly became true for Krys Shelley, who is now a carpenter and volunteer advocate for the California Coalition for Women Prisoners, and for Kruzan, who visits girls in juvenile detention with a message of “hope that’s tangible.”

But none of this healing or rehabilitation would have been possible were it not for advocate groups, pastors, and concerned citizens who stopped to listen to their stories with deep context—and demand that the courts do the same.

“Hurt people hurt people,” Stauring said before connecting me to Kruzan via phone. “But healed people heal people. They become the best teachers our communities have ever seen.”

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!