Apr 20, 2016

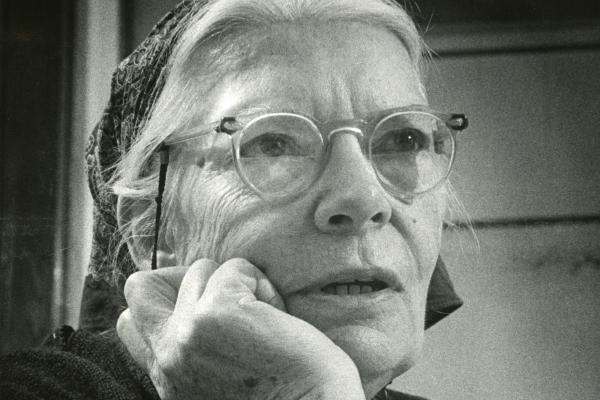

The famous Catholic Worker activist Dorothy Day once remarked, “Don’t call me a saint. I don’t want to be dismissed that easily.” That hasn’t stopped the Archdiocese of New York, however, from moving forward with a “canonical inquiry,” the next step required to become eligible for beatification and then canonization, when a figure officially becomes a saint.

Read the Full Article

Already a subscriber? Login