Mar 8, 2016

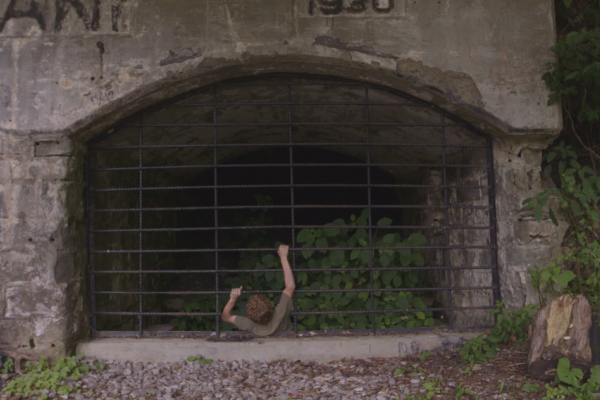

I was always going to make a film about prisons, but from the outside of the prison itself. I wanted to challenge the alienation we feel by seeing prisons simply as buildings we have no relationship to. I had originally thought I was just going to set it in one city. For example, when you look at the prison population in New York State, a lot of those prisoners come from a small section of neighborhoods, and I was originally thinking of setting the film in those places.

I ended up going on a longer journey, with a goal to disrupt the identity of these areas we think of as “free,” to reveal how deeply prisons influence our lives in all spaces.

Read the Full Article

Already a subscriber? Login