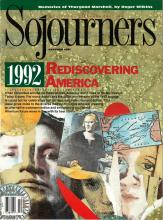

The storms Christopher Columbus encountered on the voyage that landed him on a Caribbean island October 11, 1492, were probably moderate compared to the tempests likely to accompany the 1992 quincentenary of that pivotal journey. The blasts are already coming from all sides, which will make both moral and political navigation difficult during what promises to be a highly symbolic and confrontational year.

It once seemed easy. All American school children learned the simple rhyme, "In 1492, Columbus sailed the ocean blue." But the color of the Atlantic proved to be less important than the colors of the many peoples whose destinies would be altered forever because of this epoch-changing event.

Of course, the real question is, Who discovered whom? Christopher Columbus was, after all, quite lost when the Nina, Pinta, and Santa Maria arrived in the "New World." It has been rightly pointed out that Columbus didn't know where he was going, didn't know where he was when he got there, and didn't know where he had been when he returned home. What he did know was what he wanted -- wealth and power, gold and slaves -- for himself and his royal patrons. One contemporary descendant of the indigenous people who welcomed Columbus and his men says that their subsequent problems stemmed from a "lax immigration policy."

The rhetoric is high and heated, and what some thought might become a "teachable moment" is quickly turning into a high-stakes ideological conflict. What is the fight really about?

Read the Full Article