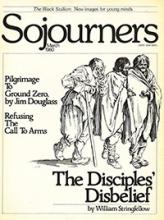

And they all forsook him and fled (Mark 14:50).

Christians are, nowadays, so accustomed to esteeming the disciples as exemplary in the faith that it seems a surprise to notice that the New Testament Gospel accounts do not report any of the disciples as believers.

Attention has focused, of course, upon Judas' betrayal and Peter's denial, amidst the tumult of Holy Week, and then upon Thomas' doubting, in the aftermath of the resurrection. This has tended to minimize or suppress the fact that none of the disciples--nor, for that matter, any one of Jesus' family--can be said on the basis of the texts as these have been received to have understood Jesus or to have either comprehended or liked his teaching or to have recognized his works or to have acknowledged his authority or to have welcomed his vocation or to have believed Jesus Christ to be the Lord of creation.

The truth, poignant as it may be, is that the disciples were profoundly skeptical about Jesus. In their experience of his ministry they were variously enthralled, mystified, bemused, apprehensive, confounded, disillusioned. During Holy Week, their elation on Palm Sunday very quickly turns into consternation; by Good Friday they have become fearful and hysterical; by Easter they are both embittered and bereft. And through all of it they remain steadfast in their disbelief.

If, for us, the disciples can be said to exemplify anything, then they must be said to exemplify not faith, but incredulity. This represents, I suggest, the most significant identification of the disciples with contemporary Christians. If any of us are to claim a biblical attitude of faith in Christ, it is necessary first of all to cope with the exemplary disbelief of the disciples.

Read the Full Article