"Unless ordinary people-people like you and me, people like my mother and father--unless we educate ourselves and work for peace, it will not happen. Our temptation is always to look to the 'experts' or the 'leaders' in government or the peace movement for the answers. But we are learning again that all of us must, and can, be peacemakers. That is what this movement is all about-ordinary people re-discovering the power to make peace a reality."

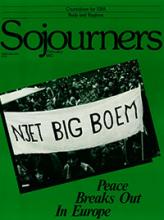

So spoke a member of a local chapter of the Dutch Interchurch Peace Council (IKV) in advance of the anti-nuclear demonstration in Amsterdam on November 21 of last year: "We are going to Amsterdam because we believe ordinary people all around the world want an end to nuclear weapons. Perhaps the beginning of that 'end' to the arms race can happen here in the Netherlands."

Indeed, it was 400,000 "ordinary people" who arose early that Saturday morning in villages and cities across the Netherlands. They packed sandwiches and thermoses of coffee and boarded buses, trains, and cars bound for Amsterdam. Four hundred thousand--twice the number expected by demonstration organizers--converged on the city. Rivulets of people streamed into the cobbled side streets. There simply wasn't enough room in the massive city square or along the designated parade route. But the fact that some people could not hear the speakers or reach the designated route didn't seem to matter. They were there, and that is what mattered. They were there standing shoulder to shoulder with strangers, smiling and singing, sharing bread and coffee, remarking to one another again and again, as a refrain: "Isn't this wonderful? Isn't this hopeful? So many people!"

Read the Full Article