ST. GEORGE'S CATHEDRAL was packed to overflowing. A rally had been planned to launch the newly formed Committee to Defend Democracy, a committee hastily put together by church leaders to protest the South African government's recent assault on democratic groups. But just hours before, the meeting was banned, along with the three-day-old organization itself. Quickly, a service was called to take place in the cathedral at the same hour the banned mass meeting would have been held.

Despite government efforts to obstruct communication, word of the service had gotten around. Police roadblocks had been set up to keep the young people from the black townships from getting to the church service in downtown Cape Town, but many made it anyway, surging into the sanctuary like a powerful river of energy, determination, and militant hope.

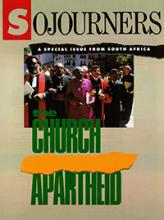

There was no more room to sit or stand in the church. People were everywhere--in the aisles, the choir lofts, and the spaces behind and in front of the pulpit. People of all human colors waited for the worship to begin and the Word to be preached. Outside the cathedral, the riot police were massing.

It was our first day in South Africa. The March 13th cathedral service provided a dramatic introduction to our 40-day sojourn in this land of sorrow and hope. Indeed, the notes struck in St. George's that day would be the recurring themes in the weeks that followed.

Read the Full Article