Rosa Parks stands tall, the light streaming behind her through the window of the bare church, her face a statement of gentle pride. Jazz singer Ernestine Anderson looks ready to explode with joy, the light above her like a halo that cascades and sparkles off the sequins of her dress.

Eva Jessye, eyes closed, face resting on her hand and cane propped between her knees, sits on a piano bench, tired but triumphant. This internationally acclaimed choral director of the Broadway production of Porgy and Bess has earned her rest -- and a place in history by her piano and in our hearts.

Septima Poinsette Clark, an unsung hero of the civil rights movement, was born in the last century. Her profile shows thin, gray hair in tight braids to her shoulders, a wrinkled hand under her prominent chin. Her portrait says dignity.

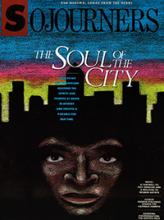

On a winter day in Washington, D.C., I walked out of the cold and into the warmth of these women and 71 of their sisters at the Corcoran Gallery of Art. The exhibit by photographer Brian Lanker was titled, "I Dream a World: Portraits of Black Women Who Changed America."

The photographs included such renowned women as Alice Walker, Coretta Scott King, Cicely Tyson, Shirley Chisholm, and Marian Anderson. But also among them were Cora Lee Johnson, who dropped out of school at age 13 and was told she didn't exist because she had no birth certificate, but went on to improve housing and health care for her people in rural Georgia; and Josephine Riley Matthews, a midwife who delivered more than 1,300 babies and graduated from high school at the age of 74.

These women are organizers and actresses, politicians and Pulitzer Prize winners; singers and Olympic athletes and college presidents; a sculptor, a storyteller, and a prima ballerina; an architect and a bishop; a neurosurgeon and a master chef. The book that accompanied the exhibit tells their marvelous stories.

Read the Full Article