I had been gone from Vietnam for more than four years, and when I got off the plane in Saigon in late February, all sorts of mixed feelings went through my head.

I thought: People yell about bloodbaths, but there have been bloodbaths ever since I've known this place. But besides the bloody side, there is an idyllic view of green rice paddies and kind, well-disciplined people running around caring for them. The people who pay for the war never quite feel all this.

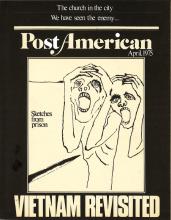

My week visit to Vietnam -- my second since I was an International Voluntary Service community worker there from 1963-67 -- changed my mind on some things. I did't realize how isolated the Saigon government is from the people. I didn't realize the sheer quantity and quality of the oppressive-repressive tactics unleashed on the population. I didn't realize as forcefully the effect of the whole Phoenix operation. Con Son Island, with its tiger cages, is just full of people who had no connection with any political side.

Since the Paris agreements of 1973, the repressive and arbitrary style of Nguyen Van Thieu's government has escalated even beyond what was present in the 1960s.

Read the Full Article