TWO WEEKS BEFORE Christmas last year, I stood with 50 other national faith leaders on the banks of the Alabama River in Montgomery, Ala., trying to imagine what it must have been like to stand on that land in 1850, at the height of the black chattel slave trade.

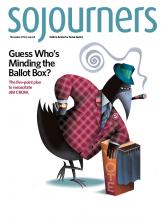

We were embarking on a one-day pilgrimage convened by Sojourners and hosted by the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI). We were there to understand one thing: the nature of the confinement and control of black bodies in the U.S. from chattel slavery through Jim Crow to mass incarceration.

Congress banned the import of enslaved people in 1808, but it did not ban the slave industry. Slave traders turned inward. Men, women, and children of African descent were sold in the Upper South; chained together with shackles around their feet, wrists, waists, and necks; and marched—often without shoes—over hundreds of miles into the Deep South for sale to farm owners desperate to meet the explosive global demand for cotton after the invention of the cotton gin.

Read the Full Article