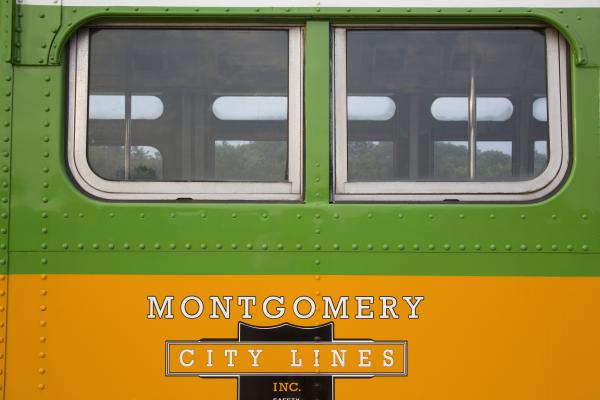

I WALKED THROUGH the halls of the Rosa Parks Museum in Montgomery, Ala.—slowly. Original documents lined the walls of the nation’s central memorial to the local actions that helped trigger the national mass movement for civil rights. To skim would have been a sacrilege. Each document was evidence. Evidence of struggle. Evidence that America’s apartheid happened. Evidence of a miracle.

The museum is like a labyrinth. Each room builds on the last, adding color and depth to a reality most of the nation has only experienced in the two-dimensional contours of sepia-toned documentary footage and pictures.

I entered the room with the kitchen table where Martin Luther King Jr. dropped to his knees and prayed, weeping, scared, and still holding onto the last vestiges of his personal dream for a middle-class preacher’s life. For my tour group, the room was about that table, but the documents lining the walls like wallpaper caught my eye.

One stood out. It was a full-page newspaper ad with a letter from the White Citizens’ Council of Montgomery to the blacks of Montgomery. The letter pleaded with the black citizens to “stop their violent attack on their city.”

The first time I read “Stop this violence,” I was befuddled. What violence?

Read the Full Article