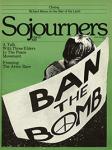

During the congressional debate over the SALT II treaty, Sojourners advocated a nuclear moratorium. The Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty did not, we felt, live up to its name. Rather than halting the arms race and reversing its deadly momentum, the treaty would have actually allowed the United States and the Soviet Union to increase their nuclear arsenals, both in quantity and in quality. The proposal for a nuclear moratorium provided a third way between the unattractive alternatives of an inadequate treaty or no treaty at all.

A nuclear arms moratorium simply means a halt or a freeze in the arms race. All further testing, production, and deployment of new and additional nuclear weapons and weapon systems would be immediately stopped. For the first time, the continual escalation and expansion of nuclear weaponry would come to an end. Obviously, this would be only the first step toward actually reversing the arms race and eventually abolishing the threat of nuclear war altogether. However, as a necessary beginning, we felt a nuclear moratorium would be decisively important. To turn around and proceed in another direction, one must first stop going in the direction in which one is already headed.

The moratorium proposal was never debated in the Senate because the SALT II treaty never came to the Senate floor. The Russian invasion of Afghanistan, the fueling of old Cold War fervor by the political Right, and the hesitancy of an insecure president seeking re-election all combined to kill SALT II.

However, the idea of a nuclear moratorium endured and has now begun to spread. Randy Kehler reports in this issue of Sojourners on how a moratorium referendum was passed by a large margin in western Massachusetts, despite the Reagan landslide. Also, Danny Collum and Mernie King describe what a nuclear arms moratorium is and what it could do.

A number of churches and peace groups are now pushing for a moratorium. The proposal has been endorsed by the National Council of Churches, and 60 U.S. Episcopal bishops recently issued a statement calling for a moratorium. Other voices from organized labor, the legal and medical professions, education, business, and the arts have recently spoken up for a nuclear moratorium. All these signs point to the possibility of a grassroots effort to place the moratorium proposal on the national political agenda, despite the alarming signs of a new military buildup.

As we have said many times in these pages, the nuclear threat is for Christians not simply a question of public policy but a matter which tests our faith. The proposal of a nuclear moratorium is a good one, and the growing evidence of support for it is indeed a hopeful sign. But Christians must go much further than advocating a nuclear moratorium.

Repentance in a nuclear age means non-cooperation with our nation's preparations for nuclear war. Regardless of what others may do, we must withdraw our consent and our support for the nation's intentions to commit nuclear genocide. The faith of the churches must be placed as an obstacle against the escalation of the arms race. This will entail risk--risking ourselves and our security for the cause of peace.

We live in perilous times. The country is controlled by fear, and the world seems increasingly out of control. Some religious leaders now suggest that the gospel must have the protection of the U.S. nuclear umbrella. Even more distressing, the rest of the church seems immobilized, unable to name such a doctrine as heresy.

In the political arena, the present assumptions surrounding the debate over military policy are so constricted as to utterly strangle the possibility of peace. If the churches limit themselves to speaking within those assumptions and acting within the acceptable political boundaries, the cause of peace will be even further diminished.

We must be turned around. That has always been the biblical meaning of repentance. Something entirely new must be tried.

Our fearful situation needs a new word, a new approach, and a new level of commitment. The moratorium proposal could be the political vehicle for such a new approach. A nuclear moratorium could take us a step closer to peace.

Jim Wallis was editor-in-chief of Sojourners when this article appeared.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!