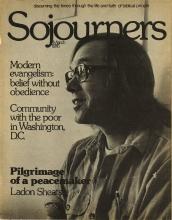

This article appeared in the March 1976 issue of Sojourners.

The virtual abolition of distinction between the private and the political realms to my mind resolves a secret of the gospel which bothers and bemuses many people of the church, though they may seldom be articulate about it. Most churchfolk in American Christendom, especially those of a white bourgeois rearing, have, for generations, in both Sunday School and sanctuary, been furnished an impression of Jesus as a person who went briefly about teaching love and doing good: gentle Jesus, pure Jesus, meek Jesus, pastoral Jesus, honest Jesus, fragrant Jesus, passive Jesus, peaceful Jesus, healing Jesus, celibate Jesus, clean Jesus, virtuous Jesus, innocuous Jesus. Oddly enough, this image of Jesus stands in blatant discrepancy to biblical accounts of the ministry of Jesus familiar to everyone (by which Jesus is known to have been controversial in relation to his family and in synagogue appearances, to have suffered poignantly, to have known complete rejection of intimates no less than enemies, and to have been greeted more often with apprehension than acclaim).

Read the Full Article