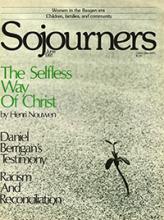

On September 9, 1980, Father Daniel Berrigan and seven others were involved in a civil disobedience action at a General Electric plant in King of Prussia, Pennsylvania, which makes parts for the Mark 12A nuclear missile. They were convicted on eight of 13 counts at their trial in Norristown, Pennsylvania, in March, 1981, during which they acted as their own attorneys. All the defendants are out of jail and appealing their convictions. Following is Daniel Berrigan's response to direct examination by Sister Anne Montgomery at their trial. --The Editors

Anne Montgomery: Father Berrigan, I'd like to ask you a simple question: Why did you do what you did?

Daniel Berrigan: I would like to answer that question as simply as I can. It brings up immediately words that have been used again and again in the courtroom--like conscience, justification. The question takes me back to those years when my conscience was being formed, back to a family that was poor, and to a father and mother who taught, quite simply, by living what they taught. And if I could put their message very shortly, it would go something like this:

In a thousand ways they showed that you do what is right because it is right, that your conscience is a matter between you and God, that nobody owns you.

If I have a precious memory of my mother and father that lasts to this day, it is simply that they lived as though nobody owned them. They cheated no one. They worked hard for a living.

They were poor; and, perhaps most precious of all, they shared what they had. And that was enough, because in the life of a young child, the first steps of conscience are as important as the first steps of one's feet. They set the direction where life will go.

And I feel that direction was set for my brothers and myself. There is a direct line between the way my parents turned our steps and this action. That is no crooked line.

Read the Full Article