“Remember those in prison as if you were there with them; and those who are being maltreated, for you like them are still in the world” (Hebrews 13:3).

Our lives are lived, for the most part, in physical, psychological, and spiritual insulation from suffering inflicted by the gross barbarities of humanity. Amidst all the decadence of contemporary North American life, there is a decency, a civility. Especially if we are white and privileged we may well have never encountered unbridled human brutality in our own experience, or that of anyone we know. And, as is so often the case, what lies not within our experience fails to touch our hearts.

Such suffering, if we know of it at all, is remote -- not our concern. We allow the environment of a privileged existence to set the boundaries of our compassion.

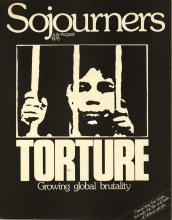

These thoughts kept running through my mind as I talked with Fred Morris, a former missionary to Brazil who had been tortured by authorities there two years ago. I had heard about torture; we’ve all seen it portrayed in movies and read of it in war stories. And it had even been one of those “issues” that has periodically entered political debate. But always it was something foreign; a topic useful in making a point, a curious and troubling human abnormality when one thinks about it (if one has the time).

Read the Full Article