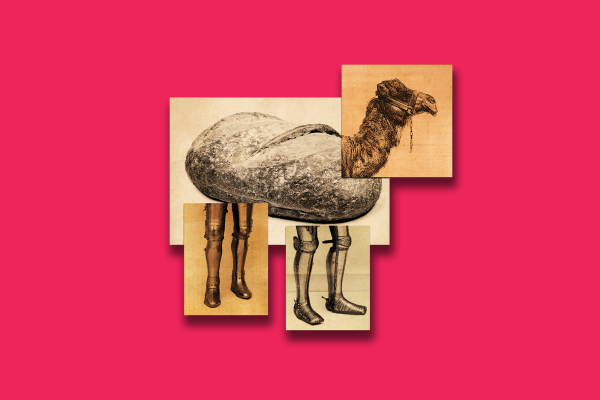

IMAGINE YOURSELF IN a darkened theater. At center stage sits a woman, child on her lap, both wrapped in tonal greys. A tiny stream of light falls from above. Off left, large animals shift their weight on floorboards, chuff-chuffing their breath; foreign tongues murmur them calm. Off right, the only sound is of metal rasps running repeatedly down the length of blades; random sparks flare off the cutting teeth. This is Epiphany. Everything is waiting to happen. We know the narrative detail: Mary and Jesus, a manger, the Magi’s star-trekking journey with camels and gifts to honor a “newborn king” (while Herod, like Pharaoh, plots a bloody offense). But Epiphany is a season for paradigm shifts. What if we scramble the details? Imagine this. Off left, the chuff-chuffing of foreign tongues come not from men calming beasts, but camels praying as they approach the child, the spiritual waterhole for the world. The camels have not brought kings or astrologers, but a guild of bakers, who extend platters of fresh bread toward the child. At center, the woman wrapped in a cloak of ultraviolet leans back on her stool: She has given birth to a star, filling them both with light. At her side stands a human child. He gazes off right. The sound of rasps and swords, boots and shouted commands fascinate him. Slowly, the child lets go his mother’s hand, relaxes his throat muscles, measures his breath. In a world of bread and circuses, he has made brothers of soldiers. He is a sword-swallower and eats their pain.

Read the Full Article