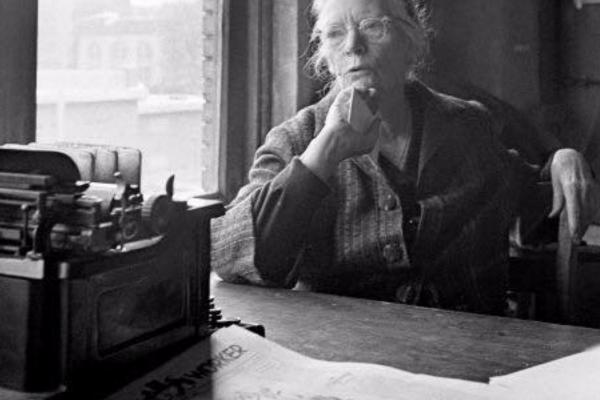

I always thought I would go to her funeral. I met her only twice, but no one affected me like she did. I was on the road when I heard, and it was too late to get to the service. The feeling of grief was overwhelming. She embodied everything I believe in. She, more than any other, made my faith seem real and possible to live. She took my most cherished visions and made them into realities. Now she was gone. It was like the end of an era.

Slowly, the grief gave way to gratitude. We were richly blessed to have had her among us, if only for a while. She was an ordinary woman whose faith caused her to do extraordinary things. The gospel caught fire in this woman and caused an explosion of love. We will miss her like a part of ourselves.

Dorothy Day died on Saturday night, November 29, 1980. She was 83. Dorothy died in her room at Maryhouse, a place of hospitality she founded for homeless women on New York's Lower East Side.

It was in the Depression year of 1933 that she and Peter Maurin founded The Catholic Worker. They sold the first copies of the newspaper on May Day for a penny each. "Read The Daily Worker" shouted the communists selling their paper to the unemployed in Washington Square. "Read The Catholic Worker daily," answered back a little band of Catholics who said their faith had made them radicals.

For 47 years their paper has been the voice of a movement that has always concentrated on the basics of the gospel. Dorothy's grasp of her times was profound, but it was the simple things that captured her imagination and commitment--like the gospel being good news to the poor and the children of God living as peacemakers.

Read the Full Article