IT HAS BEEN A TIME of shadows and warnings, bursts of violence and the creeping stain of betrayal. Falsehoods, at first a dripping faucet over a tin bucket—the hint of failing seals and valves, the promise of future corrosion—have become a downpour. Disintegration seems the rule.

Where to find a true story, one that endures?

Scripture might seem the logical turn for a Christian. But I know my weaknesses. Left to my own devices, I cherry-pick favorite verses, I swerve away from difficult passages. I rarely read anything in the Old Testament except the prophets—and those while too often presuming I stand with them, already on their side, and God’s: Nothing for me to hear, except the echo of the woe and correction I’d like to dole out to others. A situational loss of hearing that is a sure path to perdition.

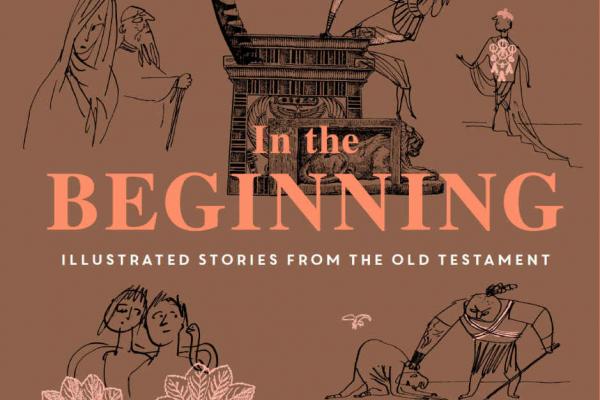

But then I was introduced to an unusual portal to the holy word, one that easily charmed its way past my conscious and unconscious scriptural biases: a 500-plus-page coffee-table book whose bronze cover is adorned with line drawings of people who are at turns winsome and ominous. With title and highlights in fluorescent orange, the design is reminiscent of some DayGlo-kissed whimsy from the 1960s. In the Beginning: Illustrated Stories from the Old Testament (Chronicle Books) retells, through images and spare prose that is both fresh and respectful of the scriptural sources, core stories of the Judeo-Christian tradition, from creation and the Garden of Eden to Daniel in the lions’ den.

Read the Full Article