“A SUGGESTION: Speak much about Jesus.” Henri Nouwen’s recommendation to a friend, captured in Love, Henri—a new collection of his personal correspondence—encapsulates the priest and author’s private and public ministry. More than almost any other modern figure, Nouwen bridged Catholic/Protestant doctrinal divides with his writing to bring spiritual healing and comfort, even as he wrestled with what he termed his inner “demons.”

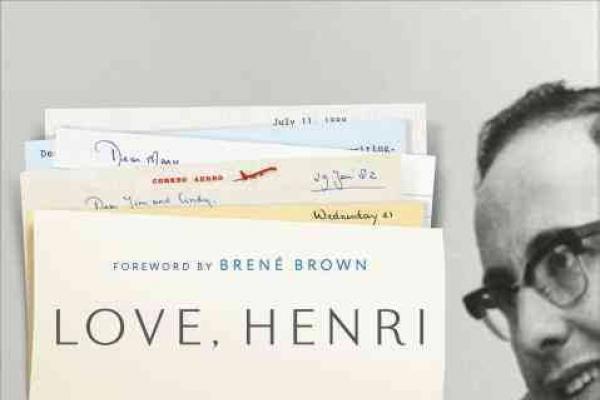

Edited by Gabrielle Earnshaw and released in conjunction with the 20th anniversary of Nouwen’s death, Love, Henri highlights the priest’s struggle for inner peace and his extensive web of deep friendships. While the collection does not present any shocking revelations, and contains fewer transcendent moments of raw emotion than other collections of Nouwen’s writing, it works well as a meditation on what it means to love selflessly and extend oneself over a lifetime.

In the collection, Henri is both protagonist and antagonist, healing and wounding those in his life. While Nouwen himself acknowledges “a kind of enthusiasm” in his own writing that “seems a little bit too easy,” the gift is watching him participate in these seeker/giver relationships. In early letters, he is often overly attached: “Maybe your distance simply means that I force myself upon you and there is not a mutuality that makes friendship possible.” Later, though, we see him “speak about [his] inner struggles as a source of self-understanding” and solidarity, rather than a way “to avoid difficult positions and responsibility and evoke some sympathy.”

Read the Full Article