It was the day before Thanksgiving when I heard the afternoon news report: Walter Fauntroy, Baptist minister and the District of Columbia's delegate to the U.S. Congress, had been arrested at the South African embassy.

I could feel my excitement rising as I listened to the details of how Fauntroy, Randall Robinson of TransAfrica, and Mary Frances Berry, member of the U.S. Civil Rights Commission, had met with the South African ambassador to protest Pretoria's recent crackdown on dissent and, in particular, the jailing of black union leaders. The three U.S. black leaders refused to leave the embassy until the South African government agreed to release the prisoners. The representatives of apartheid said no, and Fauntroy and the others were arrested for their protest. Now they were prisoners too.

There have been precious few occasions in my life when I have felt proud of my elected officials. This was one of those rare days.

On Thanksgiving Day we had a neighborhood feast for all the people in our neighborhood food distribution line. For the poor and hungry of Washington, the act of civil disobedience by black leaders was quickly understood and warmly supported. Many talked about the old days of the civil rights movement when such tactics were at the heart of a movement for conscience and change. The people knew about South Africa, and they too were proud of their Congressperson. The next week, many pinned red solidarity ribbons on their coats.

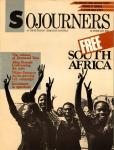

Since November the South Africa protests have grown daily and spread throughout the country. Something has been sparked, and even the organizers have been surprised by the breadth and intensity of what has now been named the Free South Africa Movement. This issue of Sojourners is devoted to that very hopeful movement that is giving life to every other movement for social justice and peace in this country and around the world.

In an interview with Sojourners, Walter Fauntroy describes the origins, progress, and future plans of the Free South Africa Movement.

Talking to Allan Boesak in South Africa by phone confirmed how important the growing U.S. protests are to the struggle there. He said, "The impact is enormous. We are under constant pressure and intimidation, but the solidarity and fellowship we feel from our friends in the United States is a great source of strength for us."

I recalled a memorable day spent with Allan and his wife, Dorothy, in my apartment in Washington, D.C., following the Twentieth Anniversary March on Washington in August 1983. They spoke of the continual threats under which they must live.

"We've had more phone calls and death threats the last few months than ever before," said Dorothy. "I answer the phone, and a man says, 'We know the routes your children take to and from school,'—then he tells me the routes—'and one day, we're going to take [the children] if your husband doesn't stop speaking out.'"

Allan said the phone calls and threats are unrelenting now, since the minister of law and order has called for his arrest. "But so far they haven't touched me, and we continue on." After the official threat to arrest Allan had been delivered on South African television, a simple message had been sent from Allan to his friends around the world: "I am fine. I am not afraid." In this issue, Allan Boesak speaks in defense of his people and himself and assesses the current situation.

THE PRESENCE of Bishop Desmond Tutu in the United States for a fall teaching sabbatical has been an important catalyst to the Free South Africa Movement. The awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize to Bishop Tutu gave this articulate prophet a platform from which to speak to the conscience of the nation and the world. Before a Senate subcommittee, he testified with a sparkle in his eyes and a joyful smile on his face, "We shall be free!" In an unprecedented gesture of respect, the senators rose to give Tutu a standing ovation. His Thanksgiving sermon, given at the Washington Cathedral, is published here, along with some comments to reporters and a personal interview with Sojourners about questions of faith and hope.

The Reagan administration is fond of making a distinction between "authoritarian regimes" where the repression is only "random" and with which the United States can work, and "totalitarian regimes" where the oppression is "systematic" and which the United States fundamentally opposes.

Nowhere is the hypocrisy and moral bankruptcy of that policy more evident than in the Reagan administration's policy of "constructive engagement" toward South Africa.

South Africa is the most systematically repressive society in the world. In no other country is racism constitutionally established by law. Apartheid is a totalitarian system—a white minority rules absolutely over a black majority—whose labor is exploited, land is stolen, families are broken up, political freedom is denied, and human rights are violated. As we have seen again in recent days, black men, women, and children are subject to being imprisoned without trial, brutalized by police, and killed by government security forces.

Apartheid is more than totalitarian. It is a disease, a moral sickness that takes the lives of its victims while corrupting the souls of its perpetrators. And to further compound the heinous sin of apartheid, it is justified in the name of Christianity. The new "Confessing Church" of South Africa has named apartheid for what it is—a heresy.

The Reagan administration speaks out loudly against the killing of a priest in Poland, but there is no outcry when hundreds of blacks are murdered in South Africa. More political prisoners in South Africa have died in detention since Ronald Reagan took office precisely because the white Afrikaner government knows there will be no protest from Washington.

The investment of U.S. banks and corporations in South Africa is growing substantially and continues to provide a bulwark of support for apartheid. The crucial role of U.S. investment in South Africa is now being made clear by the Free South Africa Movement, and the justifications offered for such investments are being increasingly revealed as hollow and morally indefensible.

UNITED STATES SUPPORT for apartheid must come to an end, and the U.S. churches should lead the way. There are no longer any good excuses. The churches should now call for moral non-cooperation, political sanctions, and economic disinvestment in regard to South Africa, and the churches' leadership role must first be by example. All U.S. church money should be immediately withdrawn from any bank or corporation that invests in South Africa. Combined with the power of nonviolent direct action, such a clear and principled decision on the part of the U.S. churches would deal a severe blow to South Africa's racist regime.

It is time for the churches in the United States to take such a decisive stand, or be willing to explain why they continue to invest in heresy. The moment has arrived, the issue is clear. It only remains for us to act.

Jim Wallis is editor-in-chief of Sojourners magazine.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!