Two years ago an outsider might have wondered if there was a peace movement in Great Britain. Since then there has been a revolution in the way people think. Diverse sectors of our society--doctors, teachers, local government authorities, rock groups, trade unions-- have now, in many places, become warm supporters of the disarmament movement.

What has caused the change? My guess is that four factors combined to put the spotlight on an arms race that had been lurching along, ignored, for many a year. The much-publicized American nuclear accidents of 1979 and '80 certainly had their effect: If a workman dropping a spanner can produce an explosion which blows a nine-megaton warhead out of its silo, and if the failure of a computer chip can twice put nuclear bombers on their runways on full alert, then the fragility of the system becomes very obvious. In a world of 50,000 nuclear weapons, one cannot afford an indefinite number of accidents.

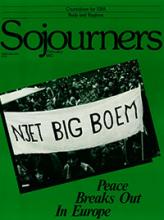

Then the decision by our government in December, 1979, to accept 160 cruise missiles in our country, which though allegedly independent already has more than 100 American military bases, created some indignation. At no point were the people of the country consulted before that decision was made; it soon became clear that, whatever military purpose cruise was meant to serve, it could only increase our chances of becoming an inevitable general target. With its "one key" system, cruise was yet another military development which only the Americans had the power to operate. In fact, of course, that aspect of things is nothing new.

Read the Full Article