“THE CONTEMPLATIVE ON her knees well knows the messy entanglement of sexual desire and desire for God,” writes theologian Sarah Coakley. If she’s right, then attending to what arouses us sensually can teach us something about how God lures us through our longing and, even, how we can attract God’s intimacy. This month, we’re exploring how queer theology can invigorate (dare I say, stimulate?) the anticipation we build throughout Advent. This approach may seem blasphemous to some who aren’t familiar with a queer-affirming lens ... and perhaps uncomfortable to some who are. Many of us are steeped in Christian body-denying theologies and moralities. We are uncomfortable meeting God in ways that are playful, erotic, unnerving, and always cognizant of power dynamics (though scripture is steeped with such sexual innuendo). Queer theology starts from (rather than argues for) not just queer affirmation, but queer celebration. It can expose the erotic dimensions of our sacred stories to reveal God’s wild and promiscuous desire for all creation.

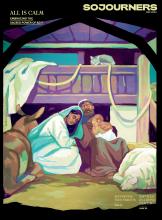

December is a season for sending Christmas cards depicting the Holy Family — perhaps the most heteronormative image in the church year: A mom and dad stare lovingly at their beautiful baby. This static image can obscure the mess of desire, power, submission, and surprising gender fluidity required to incarnate this Holy Child. What moves in us as we ponder the design of different Christmas images that don’t shy away from this beautiful mess? What images help us face the wonder and terror of what it feels like to be undone and remade by God’s overcoming?

Read the Full Article