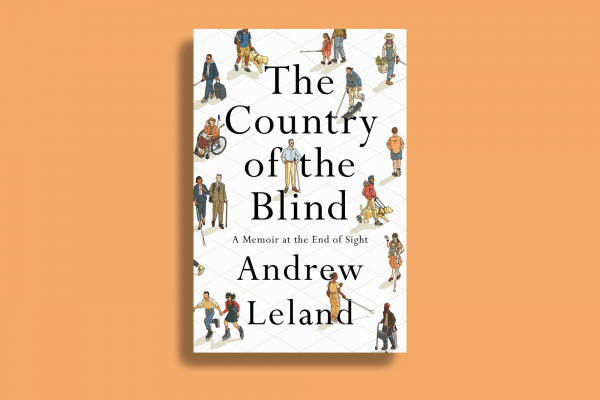

ANDREW LELAND HAS been going blind since high school. In college, he was formally diagnosed with retinitis pigmentosa, a degenerative eye condition. Leland, who is a writer, editor, and educator, named his memoir The Country of the Blind, after the 1904 H.G. Wells short story in which an explorer falls down a mountain and finds himself in a village where everyone is blind. But unlike the explorer, Leland does not experience a rapid descent into blindness. Instead, for decades he has traversed the blurry middle ground of “becoming blind.” He writes, “It’s so much easier to conceive of it as a binary — you’re either blind or you’re not; you see or you don’t.” The Country of the Blind breaks down the binaries of our understanding of blindness and sightedness, and takes us on a personal and historical journey through the culture of blindness.

Blindness has always been a part of my story. My father, who has both retinitis pigmentosa and Coats disease, started to lose his eyesight in his teens and lost almost all of it by the time he was 27. But his world was not lost when blindness set in. Rather, like Leland and others with blindness, his world was still there; he just needed to learn new ways to traverse it. Growing up, I observed my father navigate the world with intention. He chopped firewood to keep us warm in the winter. He identified different denominations of currency by distinctively folding the bills. He carried a special tool to guide his pen when he signed documents.

Read the Full Article