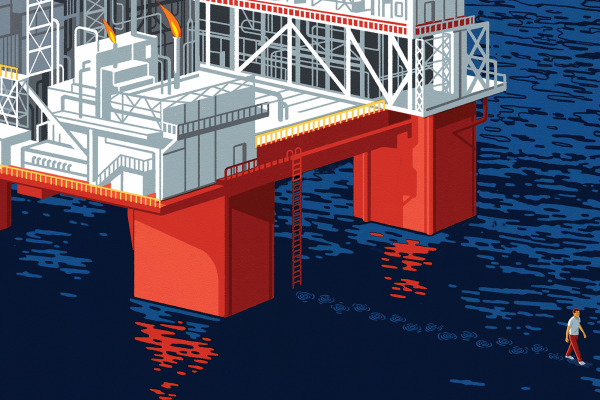

FOR MANY OF us, this summer felt like a cosmic wake-up call about climate change. Fire, floods, hurricanes, and other cataclysmic signs of our rapidly heating planet seemed to offer near-apocalyptic warnings that we’re approaching a make-or-break point, especially for those already vulnerable because of poverty or geographic location. We almost didn’t need the scientists—such as those who produced the dire U.N. report in August—to once again sound the alarm, as they have done so many times over the past several decades, nature already having done the job in her impossible-to-ignore fashion.

Anger seems an apt response to global warming, given that the world’s climate crisis isn’t an unavoidable act of nature; rather, it’s rooted in intentional actions by people seeking power and wealth. The main perpetrators—including ExxonMobil and its GOP enablers—knew about the causes of climate change more than four decades ago and, as Scientific American put it, “spent millions to promote misinformation” and manipulate public opinion. Some might call such duplicity “crimes against humanity” and “indictable behavior.”

Read the Full Article