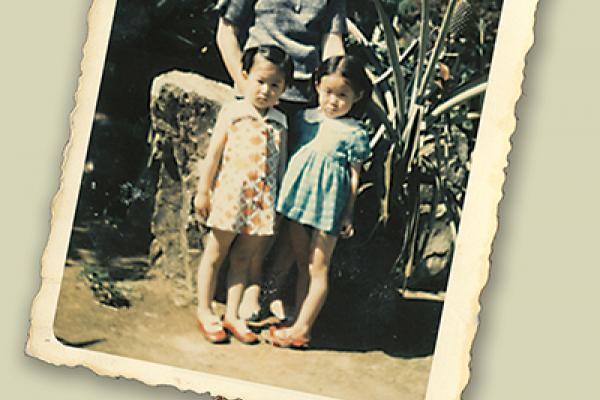

MY FAMILY EMIGRATED from South Korea to Canada in 1975 when my sister and I were 6 and 5 years old, respectively. Before I left Korea, I had no idea where Canada was. With our mother, we boarded a plane that took us to Hawaii, then Alaska, and finally Toronto.

Korean was the only language I had ever spoken. I assumed that everyone spoke Korean. I had no idea what people were saying when I arrived in Toronto. My uncle in Korea gave my sister and me each a cute little necklace to wear with our name, address, and phone number written on the back of it. It was a round red necklace with a picture of an adorable puppy. We wore it around our necks on the plane so that if we got lost, we could more easily ask for help to find our way home.

After 40 years of carrying the necklace with me as I moved from place to place, my children threw it into the garbage last year as they were doing spring cleaning. They thought it was a piece of junk. It may look like junk, but to me it provides a special reminder of my childhood, family, and the home from which I emigrated. Luckily, I liberated it from the garbage before trash day. Now I keep it safe as one of my prized possessions, one of the few things I have left from Korea and from my childhood.

My necklace reminds me from where I have come, what I have experienced, and what I have endured. As my necklace has survived all the moving and tossing around in my life, I too will survive.

As an immigrant family, we had few earthly possessions. We lived in a two-bedroom, cockroach-infested apartment. I had only one little hand-me-down toy doll that someone passed on to me rather than throwing into the trash. My library consisted of a few books that I read over and over. My parents had one car, and they worked different shifts, so they were rarely home at the same time. There was no car at home to drive us to the library to sign out books. After awhile I allowed my creativity to run wild and made up imaginary stories based on the pictures in the few books we had.

Read the Full Article