As I wandered through the exhibition hall at the Episcopal Church's triennial General Convention in Anaheim, California, September, I was struck by how many of the old familiar faces were missing. A sign of aging and a signal I've attended too many of these since my first in 1970, I thought.

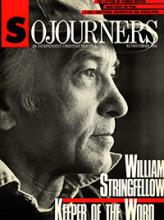

I missed the retired and otherwise engaged—Henry Rightor, Paul Washington, Muhammad Kenyatta. But mostly I missed the dead—Pauli Murray, Denzil Carty, Marion Lelleran. Most of all I missed Bill Stringfellow, for it was in the context of solemn assemblies and attendant late-night strategy conclaves in interchangeable hotel rooms across the country that I knew him best.

Bill was of course famous in Episcopal circles and on the lecture circuit from his East Harlem days in the late '50s and early '60s. I never met him then and viewed him somewhat the way I viewed C.S. Lewis—as an enthusiasm of my co-religionists that I couldn't get very excited about. Bill's circle did not include many women, and I assumed, erroneously as it turned out, he would have little interest in the women's movement.

I did not meet Bill until after the "irregular" ordination of 11 women in Philadelphia in July 1974. He was not at our ordination, though one of the bishops had asked him to stand by in case legal help was needed. He was fogged in at his home on Block Island. However, he did get to the House of Bishops meeting in Chicago two weeks later when the bishops declared no ordination had taken place in July. It was after that fateful and ill-advised declaration that we sat down for our first hotel-room strategy session.

Bill knew more about the Episcopal bishops and how they interacted than anyone else in the church, including the bishops themselves. Episcopal bishops fascinated him. He'd written at length about them in his two books on Bishop James Pike. He respected the episcopate and wanted desperately to see the men in it lead the church courageously and competently.

Read the Full Article