The 15th Amendment to the United States Constitution was the third in a triad of amendments crafted to protect the rights of recently emancipated African Americans. The 13th Amendment abolished slavery. The 14th Amendment granted citizenship to people who were once enslaved, regardless of race. The 15th Amendment, which was passed by Congress February 26, 1869 and ratified February 3, 1870, reads:

Section 1.

The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude —

Section 2.

The Congress shall have the power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

It took nearly a century of blood, terror, and tears, but in 1965 President Lyndon B Johnson and the 89th U.S. Congress passed the Voting Rights Act of 1965; legislation to enforce the 15th Amendment. Finally.

One year more than a decade later, in 1976, I walked hand-in-hand with my mother trudging up and down city blocks lined with row houses in our West Oak Lane neighborhood of Philadelphia. Each time we knocked and a neighbor came to the door, my mom, who served as the judge of elections for our neighborhood, asked: “Are you registered to vote?” If they weren’t, out came the clipboard.

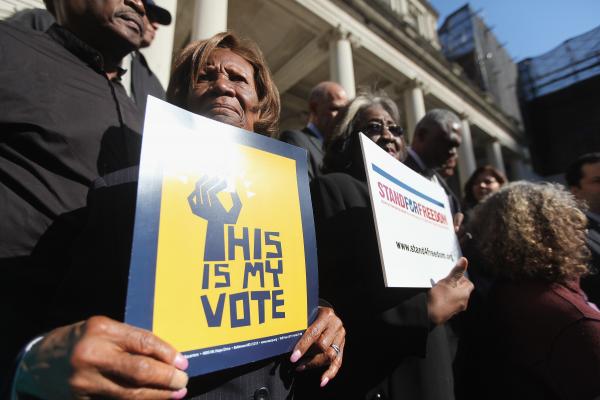

I didn’t understand the legacy we were a part of that day, but with each sweep of the clipboard we were brandishing a non-violent weapon in the long fight of our ancestors to be and stay free. For 100 years — that’s five generations — they faced down the terror of burning crosses, threats to life and livelihood, and the elaborate labyrinth of Jim Crow voting laws — all set up to suppress their votes, all set up to crush their ability to exercise dominion.

So, when the Supreme Court announced recently that one of the cases it would take up in this session was a challenge to Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, the hairs rose on the back of my neck.

Read the Full Article