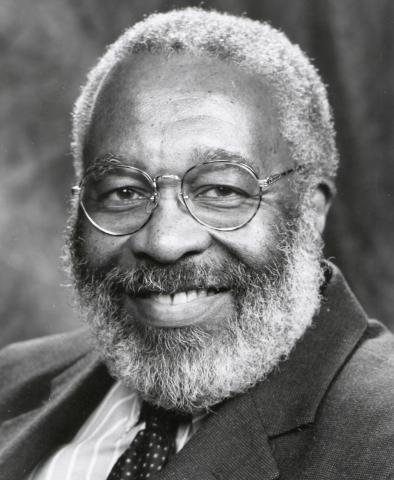

Vincent G. Harding was a Sojourners contributing editor and a professor at Iliff School of Theology in Denver.

Posts By This Author

From Harlem, With Love

James Baldwin did not allow us to take the easy route of mesmerizing guilt or undemanding fear.

James Baldwin was widely known as the most eloquent literary spokesperson in the black struggle for equality during the civil rights movement. A novelist, playwright, poet, and essayist, he was said by reviewers to have been able to "make one begin to feel what it is really like to have a black skin in a white man's world." Among Baldwin's works are Go Tell It on the Mountain, Another Country, and The Fire Next Time. Baldwin died of stomach cancer, on December 1, 1987, at his home in southern France, where he spent much of his life following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968. He was 63. The following reflections on James Baldwin are offered by Sojourners contributing editor Vincent Harding, who was a professor of religion and social transformation at Iliff School of Theology in Denver, Colorado when this article appeared. -- The Editors

We have lost a great lover.

That was clear at the beginning of December when the first telephone call reached me, bearing the stunning news of James Baldwin's death. It is even more apparent now, as the more measured rhythms of monthly journalism deadlines move us beyond the initial shock and sadness, inviting us to extend, and thereby deepen, our mourning and our remembering. Indeed, now it is possible to carry Jimmy's memories into all the ambivalent national celebrations of his friend, Martin King, as well as to let his powerful sense of the humanizing uses of tragedy illuminate the meaning of what we call Black History Month, observed each February.

Such a conjunction of recollection and hope is more than accidental, for Baldwin cared deeply about King and understood his "much-loved and menaced" younger brother far better than most of us. In the same way, it is surely the case that no one in our generation felt more deeply or expressed more eloquently all the harshened beauty and the creative significance of the African-American pilgrimage on this soil. And now Jimmy continues his own journey -- relieved, I trust, of the continuing anguish which inhabited his fragile but resilient being here on earth.

I shall miss him. Having begun where he began, in Harlem (his seven-year start on me and a variety of different life-choices did not allow us to meet consciously until the Southern freedom movement brought us together -- but I know our earlier steps must have met somewhere on the beleaguered streets of our hometown), having crossed paths and shared hopes and fears together in a variety of other times and places, I am tempted to feel a special, personal loss.

But neither Jimmy's pain nor his love could ever be monopolized. He quite literally belonged to us all whether we wanted him or not. And that was his great gift, his awesome, sometimes terrifying, offering -- terrifying, partly because he saw and spoke and wrote so much that we recognized as truth, partly because he challenged all of us to link arms and lives and walk through the purifying fires with him.

Forward Toward the Dawn

We have seen the many faces of hope. It has met us along the way in a fascinating variety of sizes and colors.

Never Too Desperate to Be Human

A black historian wrestles with issues of race, peace, and faith

The Land Beyond

Reflections on Martin Luther King's 1967 speech, "Beyond Vietnam"

Image via Seattle.roamer / Flickr

This article originally appeared in the January 1983 issue of Sojourners.

Somehow Martin King refuses to die within us, among us. Fifteen years after it was delivered, his historic Riverside Church speech, "Beyond Vietnam," reappears and thrusts upon us a King we had largely chosen to forget. Even now it would be tempting to take this cry from the heart of a driven, searching, magnificent brother and file it away as a document for museums and other honorable places.

But neither the fiery signals rising from some of our latest potential Vietnams in Central America, South Africa, or the Middle East, nor the mounting anguish of the betrayed and disinherited of our own land will allow us to escape the unresolved issues of the past or avoid the costly and accurate vision of our comrade in the faith. The speech not only requires us to struggle once more with the meaning of King, but it also presses us to wrestle as he did, with all of the tangled, bloody, and glorious meaning of our nation (and ourselves), its purposes (and our own), its direction (and our own), its hope (and our own).

Recently the name of Martin Luther King Jr. has been in the public arena primarily as the person whose birthday should or should not become a legal holiday. But this rather smoothed-off, respectable national hero is not the King of "Beyond Vietnam." Those who have, with all the best and most understandable intentions, pressed for King's birthday as an official holiday seem to have enshrined the King of 1963. In a way, that is a more comfortable image for us all: the triumphant King of the March on Washington, calling a nation and a world to a magnificent dream of human solidarity.

But all that,was before the assassins' bombs ripped out the life of the Sunday School children in Birmingham, before the fires of rebellion scourged the northern cities and moved King into Chicago, before the cry of black power was raised, before courageous and radical spokespersons like Malcolm X and the leaders of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) had begun to testify against the steadily rising tide of destructive U.S. imperialism in Vietnam, before King decided to break what he called the silence of betrayal and speak his own truth concerning his nation's role in Vietnam and in all the world's non-white revolutionary struggles.

Sometimes we wish to forget that by April 1967, King was a beleaguered public figure. He had refused to join the fearful litany of condemnation mounted by the civil rights establishment against the militant demand for black power, and for that he was fiercely attacked by moderates and liberals. On the other hand, some of the younger black and white radicals seemed to think that their best contributions to revolution were measured by the harshness of their criticism of King's nonviolence and "moderation."