Beatrice M. Spadacini is an Italian American freelance writer based in Silver Spring, Md. She writes about global social justice issues, human rights, and health. In 2023, she received the One Health award for her work as the manager of the Internews Health Journalism Network and her efforts in mainstreaming the One Health approach, which highlights the intersection between people, animals, plants, and their shared environment. Bea is the former executive producer of the One in Four podcast, a project focused on uplifting the voices of the formerly incarcerated and reframing the narrative around reentry from prison in the United States. Bea’s byline has appeared in the Christian Science Monitor, Sojourners, The Guardian, il Corriere della Sera, Noi Donne, The East African, La Voce di New York, and Internazionale weekly. Bea is also a certified kids’ yoga teacher, a potter, and a nutrition conscious Mom. More at www.beaspadacini.com.

Posts By This Author

Giving Birth While Shackled to a Bed

The United States has the highest female incarceration rate in the world. What does that mean for mothers in prison?

KADIJA CLIFTON LEARNED she was pregnant with her second child while being booked at a Maryland county jail. She had no idea that she was expecting. She was halfway through her pregnancy before she got her first ultrasound. On that day, two armed sheriffs escorted her to the medical facility with her wrists cuffed in front of her belly. A female correctional officer sat in the corner of the room while she was being examined. Clifton felt she had no privacy — “it was invasive and not fun at all.”

Clifton, who has been out for several years and is raising her son with her parents’ support, recalls that she spent the rest of her pregnancy in the county jail worrying about the health of her unborn child. She was already anxious about leaving her then 5-year-old daughter to be raised by her ex. The news of the pregnancy made things even more complicated.

“During those months I remember simply wanting a comfortable place to sit, versus plastic chairs or stools with no back support. I was seriously pregnant,” says Clifton. “Then there was the food, or lack of it. You have a limited amount. You get three meals a day, and if you are pregnant, it is just not enough.” Luckily, by the time Clifton was due, she was able to pay the bail bond and was awaiting trial at home.

I first met Clifton at a graduation ceremony in Alexandria, Va., for Together We Bake, a workforce training program. Clifton shared her life story in front of a handmade collage while hugging her then-5-year-old son. She had completed a 10-week training, learning about food safety, business administration, job readiness, and other critical life skills. Two months later, she became a senior adviser to a podcast on reentry I was producing at the time. Clifton now works as a night supervisor in a facility that hosts at-risk LGBTQI+ youth. Her daughter, now 14, still lives with her dad, but she and Clifton speak regularly.

Banking on Freedom

Your retirement plan may be supporting mass incarceration. But socially conscious investors are trying to change that.

Brian A. Jackson / Shutterstock

LAST JUNE, COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY sold all of its shares in the Corrections Corporation of America, the largest private prison corporation in the country, and in G4S, the world’s largest private security firm. In doing so, Columbia became the first U.S. university to completely divest from the $74 billion prison industry.

Though the total amount Columbia divested, roughly $10 million, was not a major financial loss for either company, it was an important win for the students who had been pressuring the university to divest since 2013. “We work in the context of a bigger movement that seeks to break down the notion that prisons and police can solve our problems,” said Asha Rosa, a student organizer with Columbia Prison Divest, part of Students Against Mass Incarceration at the university. “We aim to create a world where people understand that investing in something like a prison is a socially toxic investment.”

Other universities and nonprofits followed suit: In December 2015, the California Endowment—a private, statewide foundation that focuses on health and justice for all Californians—announced it will no longer make direct investments in companies profiting from for-profit prisons, jails, and detention centers. A few weeks later, the University of California divested $25 million. And similar student-led divestment campaigns are underway at universities around the country, including UC Berkeley, Brown, Cornell, and the City University of New York.

For many organizations, the decision to divest from the prison industry is rooted in the organization’s own mission. Divesting is about not wanting to invest “in anything that hurts the people we are trying to support,” explained Maria Jobin-Leeds, a board member of the Schott Foundation and the Access Strategies Fund, two foundations committed to improving the lives of underserved communities, including communities of color. And given the disproportionate impact that mass incarceration has on people of color—in a 2015 speech, President Obama cited a “growing body of research” that shows people of color are more likely than whites to be arrested and more likely to be sentenced for similar crimes—both foundations decided to divest. “Companies that profit from prisons make money off the poorest and are supported by a deeply racist system,” said Jobin-Leeds. “We do not want to make money off this system.”

Profiteers and private prisons

But despite this conviction that divesting was the right move, Jobin-Leeds and her fellow board members realized it wasn’t easy to determine which investments were connected to the prison industry. One reason this was difficult was because of the overall lack of transparency within the prison industry. So while an investor could reasonably deduce that the Corrections Corporation of America manages prisons, she wouldn’t necessarily know that the CCA—like many private prison management companies—has a financial incentive to keep more people in prisons. Which it does: According to a 2013 report, 65 percent of private prison contracts with state prisons regularly stipulate occupancy quotas requiring the state to make payments for empty cells—a de-facto “low-crime tax.”

Rewriting a Prison Sentence

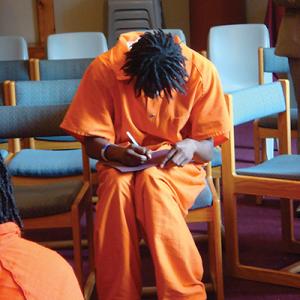

Thanks to the Free Minds Book Club, incarceration isn't the last word for young inmates in Washington, D.C.

CRIMINAL JUSTICE REFORM in the United States is gaining momentum with each graphic video showing fatal police abuse. In the aftermath of the many deaths of unarmed black men and women and the city-wide protests that erupted in Ferguson, Baltimore, and Cleveland, it is not surprising that presidential hopefuls are making bold public statements about the need to change a system that is profoundly unjust, overly punitive, and excessively costly to run.

At the other end of the spectrum, away from TV cameras and political wrangling, activists such as Tara Libert and Kelli Taylor, co-founders of the Free Minds Book Club and Writing Workshop, are dealing with decades of draconian anti-crime policies that have resulted in mass incarceration rates marked by racial disparities that have had a devastating impact on families and communities.

The numbers speak for themselves. Although the United States makes up less than 5 percent of the world’s population, it has nearly 25 percent of its prison population. According to The Sentencing Project, a research and advocacy organization working to reform the U.S. criminal justice system, more than 2.2 million Americans are now locked up in prisons and jails across the country—a 500-percent increase over the past 30 years. Furthermore, those who are incarcerated come largely from the most disadvantaged segments of the population.

Fighting for Their Lives

Women's advocacy groups in Kenya take on the issues that most hit home.