The writer James Baldwin’s 1967 New York Times essay “Negroes Are Anti-Semitic Because They’re Anti-White” is a passionate indictment of white Jewish racism and a condemnation of antisemitism. His essay is clear-eyed and right about most things — except for its thesis.

When Baldwin was writing in the ’60s, the most high-profile expressions of Black antisemitism probably came from Black nationalist leaders like Elijah Muhammad of the Nation of Islam; Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. also noted that the prevalence of white Jewish landlords in Black communities fed some prejudice. But today, Black antisemitism looks different: The Black cultural icon and self-professed Christian Ye, formerly known as Kayne West, has become infamous for his repeated, repulsive antisemitic statements.

Outside of music, Ye was previously known for his rebuke of President George W. Bush and the Bush administration’s handling of Hurricane Katrina, famously stating that “George Bush doesn’t care about Black people.” Years later, he’s since praised Hitler, engaged in Holocaust denial, and said, “I’m going death con 3 on JEWISH PEOPLE.” He’s also appeared with and boosted the political commentator and white Christian nationalist Nick Fuentes.

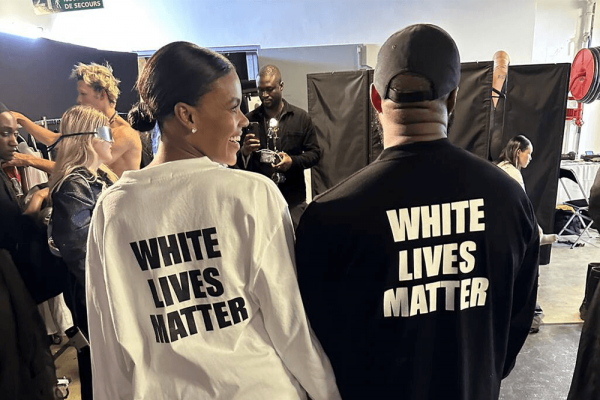

But Ye has very much not been protesting white supremacy. Instead, post-Trump, he has made a number of inflammatory racist statements directed toward Black people. Hesaid, for example, that Black people made the “choice” to be enslaved for 400 years. And in his fashion line, he included a shirt with the slogan “White Lives Matter.” That’s literally a white supremacist slogan.

People like Ye challenge Baldwin’s thesis that Black Americans’ antisemitism is really a byproduct of their being anti-white. On the contrary, antisemitism today, like anti-Black racism, tends to be one means among many of recruiting people of various backgrounds into a coalition that revels in a smorgasbord of hatred — including hatred of both Jews and Black people. That coalition in the U.S. is Christofascism — an ideology of white Christian supremacy which dreams of enforcing Christian hegemony and traditional gender roles through the imposition of an authoritarian theocracy. Christofascists implicitly, and often explicitly, target both Black and Jewish people. So, it’s important to understand how a coalition that threatens both Black and Jewish people can take advantage of fault lines that separate the two groups.

Baldwin’s essay, contra its title, isn’t primarily an effort to investigate the roots of Black antisemitism. Instead, Baldwin’s main goal is to explain, to Jewish and white people, why the example of Jewish suffering in Europe and Jewish success in the U.S. is not applicable to Black people, either as a contrast or as an exhortation.

Baldwin, who was born and raised in Harlem, N.Y., points out that in the segregated New York where he grew up, Jewish people were often the landlords and shopkeepers exploiting his family. As far as Baldwin and other Harlem residents were concerned, these Jewish people behaved like, and had the power of, white Americans and historically white American institutions. And while Jewish people had certainly suffered in the past, Baldwin observes that their suffering mostly served to validate and legitimize how far they had come. “One does not wish, in short, to be told by an American Jew that his suffering is as great as the American Negro’s suffering,” Baldwin wrote. “It isn’t, and one knows that it isn’t from the very tone in which he assures you that it is.” Baldwin isn't denigrating or denying the Jewish experience of suffering; he just observes that white Jewish people in the U.S. have been recruited and accepted into whiteness. Black people have not.

Baldwin is careful to note that, while individual Jews who are perceived as or treated as white may exploit and oppress Black people, “It is not the Jew who controls the American drama. It is the Christian.” The last line of the essay reads, “The crisis taking place in the world, and in the minds and hearts of black men everywhere, is not produced by the star of David, but by the old, rugged Roman cross on which Christendom’s most celebrated Jew was murdered. And not by Jews.”

Baldwin does not blame white Jews as a group for a Jewish conspiracy. Instead, he criticizes white Jews as individuals for their complicity in the larger system of white supremacy which has its roots in Christian theology. Baldwin understands that hating Jewish people or believing that they secretly run the world is misguided, both empirically and strategically, because it focuses ire on the wrong target. The right target, for Baldwin, is whiteness as wielded, most directly, by white Christians.

Baldwin is, I think, correct when he argues that white Jewish people are complicit in the system of white supremacy. Jewish World War II veterans built wealth through the GI program from which Black people were excluded; Jewish day schools were organized as part of the backlash against school desegregation. In Baldwin’s time, he notes that white Jewish people were able to own stores while Black people mostly could not, even in their own neighborhoods. Today white Jewish people — like all white people in the U.S. — still overwhelmingly live in segregated communities and send their children to segregated schools. Some high profile white Jewish people, like former Trump official Stephen Miller, have pushed inflammatory racist campaigns and racist talking points. So, again, white Jewish people are complicit.

But today, racialized categories are not as strict as they were when Baldwin was writing in 1967. In Baldwin’s time, intermarriage was still a very limited phenomenon, and most Jewish people in the U.S. were, by many American cultural and racial categories, classified as white. Fifty years later, though, there are many more Black Jewish people. Adam Serwer, a staff writer at The Atlantic, has written powerfully about how much he, a Black Jewish person, was affected by the antisemitism of Louis Farrakhan and the Nation of Islam. It’s much more difficult to make the case that Black antisemitism is merely a stand-in for resistance to whiteness when many Jewish people who aren’t white are still the target of antisemitism and anti-Black racism.

The most forceful challenge to Baldwin’s thesis, though, is the fact that many of the highest profile Black people who embrace antisemitic conspiracy theories today do not do so to critique whiteness. Rather, they express antisemitism alongside an explicit or tacit alliance to a Christofascist program of white supremacy that seeks to establish a white Christian nationalist authoritarian regime in which Black people and Jewish people will be, at best, second-class citizens.

In addition to Ye, consider the example of Candace Owens a Black, Christian conservative political commenter. Owens said that it would have been fine if Hitler had just wanted to rule Germany and “make it great” as long as he had not invaded other countries. Not only is this revisionist history, but it also ignores what Hitler did to Jews in Germany. Owens has also claimed that “White supremacy and white nationalism is not a problem that is harming Black America.”

Owens isn’t targeting Jewish people because she is anti-white supremacy, per Baldwin's formulation. Rather, Owens’ antisemitism is consistent with her own defense of anti-Black racism. Owens denies white supremacy is a danger to Black people, and erases Hitler’s threat to German Jews. In both cases, she apologizes for and enables Christofascist bigotry that targets Jewish people and Black people alike.

For a complementary example of how anti-Black racism can lead to antisemitism, look no further than the white, Jewish conservative Ben Shapiro. Shapiro loves to rant about “Black on Black crime” — a common racist trope — and he also loves to amplify antisemitic attacks on other Jewish people. Shapiro and Owens are colleagues at the conservative news website The Daily Wire and while they occasionally disagree about the exact scope and shape of acceptable bigotry, their shared commitments to racism generally help them bond over antisemitism — just as their shared commitment to antisemitism draws them together to promote racism.

Baldwin saw that antisemitism didn’t help Black people organize against Christian white supremacy. But he didn't quite see how white Christian reactionaries could use various bigotries and prejudices to build a coalition of hate. For some Black Christians, like Ye or Owens, Christofascism is appealing because it offers them psychological and material benefits — feelings of superiority, access to networks of power, influence, and money. Some white Jews embrace Christofascism for similar reasons.

“All racist positions baffle and appall me,” Baldwin writes. We are living at a time where it is becoming more and more clear that all bigoted positions lead to the same position and the same coalition. Declaring that “Jews run the world” or that “the globalists” must be defeated is not an expression of resistance to whiteness or capitalism; it is (like racism) a gateway to Christofascism.

Hate has one logic and one end, and Jewish and Black people alike, as well as all those who oppose Christofascism, bigotry, hate, and authoritarianism, have a self-interest in making sure that end never comes about. Baldwin wasn’t right about everything. But he was always on the right side.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!