Apr 18, 2018

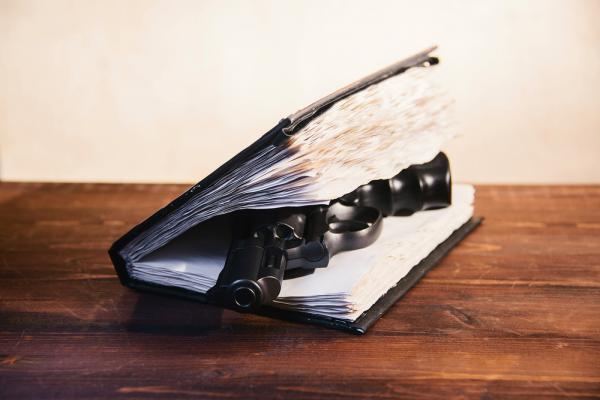

Who wouldn’t want to defend the right to a glorious eternity? Who wouldn’t fight to defend that salvation, wouldn’t carry a gun if that’s what they were told was necessary?

Read the Full Article

Already a subscriber? Login