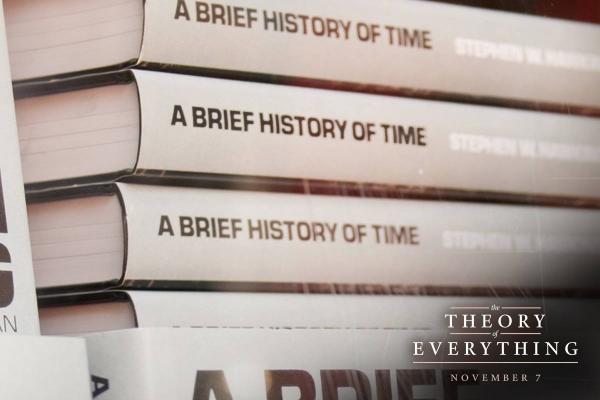

The new Stephen Hawking biopic The Theory of Everything, presents the relationship between the famed physicist and his first wife, Jane, in beautiful display. Screenwriter Anthony McCarten described the underlying theme of the film such:

“If all of us were some kind of cosmic accident, what chance love? That’s the point at which science breaks down, and something else exists.”

That rift between the proofs and facts that drive Hawking (played by Eddie Redmayne) and the “something else” represented by the inspiring story at its center is one that reflects a larger conversation about faith, science, and the unknown that feels like it’s been a part of culture from the beginning of time (all puns aside). It’s unfortunate, then, that the film doesn’t take the opportunity to explore those discussions beyond the surface level.

Read the Full Article