Sep 26, 2019

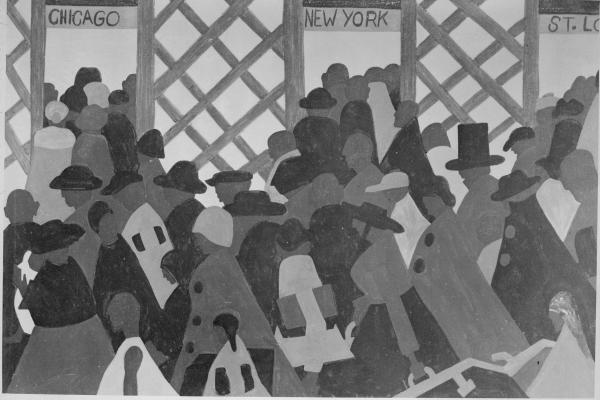

Much like Isaac from the book of Genesis, I am the son of a family seemingly destined to transience.

Read the Full Article

Already a subscriber? Login

Much like Isaac from the book of Genesis, I am the son of a family seemingly destined to transience.