As the credits rolled after Looper in a packed Chinatown movie theater in Washington, D.C., I simply sat in reverent silence. Moviegoers on all sides began to rise and quietly leave the theater, but for a brief moment all I could do was just sit there. Quite simply, the movie blew my mind.

When I snapped out of it my thoughts started racing, analyzing the ending, which I won’t ruin for you, and the movie as a whole. It wasn’t a question of whether it was “good” or captivating — those were givens. Rather, I started mining the film’s rich themes and questions, particularly what it said about love.

While sitting there, lost in my mind, I began to notice the music accompanying the names moving onscreen. The song’s chorus sang something like, “I loved you so much that it’s wrong.”

I don’t think the song choice was an accident.

That lyric, I think, illuminates the crux of the film: can something like “Love” — not just romantic love — become perverted? Or, in other words, can our love for one person lead us to do horrible things to others?

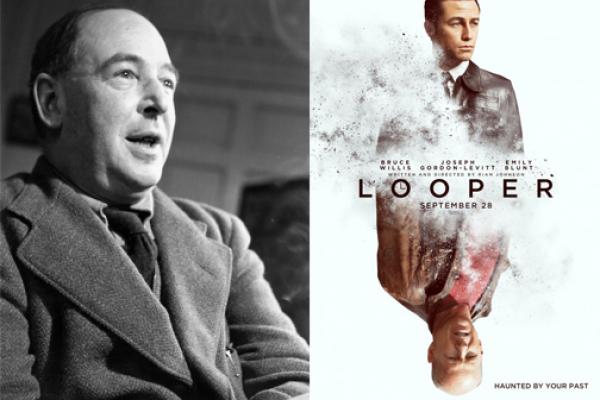

Having studied C.S. Lewis for a term at Oxford University last fall, the question almost immediately reminded me of a character in Lewis’ The Great Divorce who is similar to two of the main characters in Looper. (Oddly enough, I won’t be drawing from The Four Loves, Lewis’ detailed examination of love.) I think Pam, the mother ghost in The Great Divorce, is a lot like both future Joe (Bruce Willis), the Joe who is sent back in time to be killed by his younger self, and Sara, the mother of a future mob don.

All three of these characters illustrate the answer to my question about love. Pam’s love for her late son, Michael, ultimately consumed her life and morphed into something selfish, hurting other family members and eating away her own life. Future Joe eventually murders children (in an attempt to kill a future mob boss called the Rain Maker) to ensure a future where Joe and his wife are both alive and together. And, lastly, Sara is willing to die for a son that will eventually kill anyone who stands between him and power.

Clearly, just from the back-story, which was by no means exhaustive, my original question about the potential perversion of love seems to be answered. I mean, it’s pretty messed up if you’re willing to shoot children out of love for someone else. It does need to be said, however, that he’s not just going on a shooting spree. Joe is trying to kill the child who will eventually become the Rain Maker, who kills his wife in the future. But Joe has a shaky lead on who the Rain Maker is, and the Rain Maker is suspected to be one of three children. So, there’s also the whole justice thing thrown in there, as Joe may be trying to avenge his wife. But Joe’s decisions seem to be made more out of a desire to be with his wife than to avenge her.

But why is that the case? How is it that something as seemingly honorable and pure as “Love” can be tainted? The Beatles claimed that love was all we needed!

Here’s where I start to sprinkle a little Lewis on the conversation.

In The Great Divorce, Pam believes that her natural motherly love for her son Michael is holy in and of itself.

However, her brother, Reginald, the one whom she is talking to about Michael, quickly corrects her. Reginald says that all natural feelings are holy when “God’s hand is on the rein” — none of them are holy in and of themselves. Her motherly love becomes holy when it is submitted to God; it must be buried, in Lewis’ words, and rise again to live forever in heaven. (Exactly what that means is a topic for another conversation.)

So our understanding of love, or at least the ghost’s understanding of love, is a little off. The first question that pops into my mind is that if motherly love (or love for a spouse) is not holy in and of itself, is it bad? Does it start as something that’s not good?

And, obviously, the answer is no. There seems to be a choice as to which way the love goes, whether it’s good or evil. Greg Boyd elaborates on this choice in Letters to a Skeptic, where he talks about the freedom required for love: “We had, and have, the potential of beings of incredible love. But that means we had, and have, the potential to be beings of incredible destruction. And we, to a large degree, make ourselves one or the other.” Our choices for love or for evil eventually become who we are, which is again another conversation in itself, but these choices do indeed start out as such — choices.

In Pam’s case, she simply chose not to let God direct her natural love for Michael and it became selfish — making her boy into a possession rather than a son.

Joseph Gordon-Levitt’s character, the present Joe, sums up both situations in Looper succinctly: “I saw a man who was willing to kill for his wife and a woman that was willing to die for her son.” The first sounds wrong, but the second could also be seen as wrong if Sara does know that her son will kill truckloads of people.

Thus, we see that without the act of submission or “conversion,” as Lewis calls it, natural love will be perverted. Pam’s brother, Reginald, explains: “There is but one good; that is God. Everything else is good when it looks to [God] and bad when it turns from [God]. And the higher and mightier it is in the natural order, the more demoniac it will be if it rebels.”

Indeed. All those characters should have read their Bibles and listened, right? Then they wouldn’t have all those problems.

But hey, if the characters weren’t flawed, we wouldn’t have an awesome movie. And then we might not be talking about love.

Brandon Hook is the Online Assistant at Sojourners.

Looper poster design by Ignition Print

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!