Mar 3, 2017

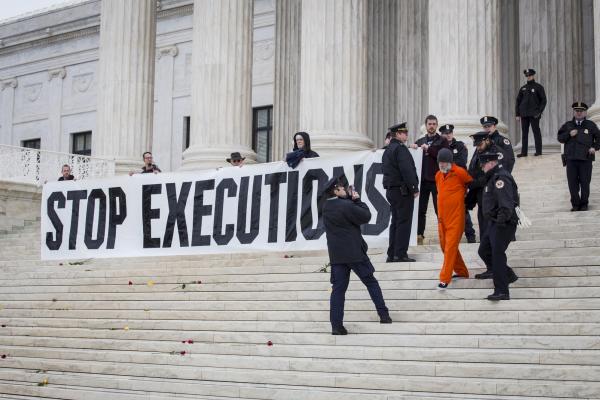

Law enforcement shackled us with chains on our hands, waist, and feet, and held us in jail for more than 30 hours. While we were there, the government that imprisoned us for holding a banner executed Ricky Gray. It does raise the question of what is right and what is wrong, doesn’t it?

Read the Full Article

Already a subscriber? Login