It was July 19, 2013, and we were leaving New York City for a spiritual retreat, six days after a Florida jury found George Zimmerman “not guilty” in the death of Trayvon Martin. The sadness, anger, and weariness was well worn on the liturgies, prayers, and preaching of many of the churches in our Harlem neighborhood.

We found ourselves joining local church leaders and a few pastors in a conversation about justice that would eventually make its way toward a broad range of matters: the gay rights of questioning teens, clean water for children in Africa, and many of the frequent places conversations go with folks who are concerned with “loving our neighbor.” And so we sat, we listened, and were genuinely moved to openly share about the challenges and opportunities that have come with cultivating safe spaces for GBLT folks in our church community. TOGETHER we also inspired one another as we offered our collective experiences with integrating the arts in fundraising for international relief efforts.

And as Jose and I sat, listened, and shared TOGETHER, we found ourselves with heavy hearts waiting …“Would the conversation broach the tragedy of Trayvon Martin?” It didn’t.

And as we sat TOGETHER in sacred solidarity with compassionate, justice-minded pastors, who happened to be white, somehow we found ourselves feeling quite alone. So we mustered the courage to ask, “How have your churches responded to the Trayvon Martin verdict?” My question was met with silence. The silence that met us did not betray aloof or timid spirits, but rather uncertainty about whether their one voice could really make a difference, or that somehow they did not have the right to “speak on behalf” of brown and black realities. And it is also important to emphasize that the silence we met is not the endemic response of all-white churches; there are many that have moved beyond the silence and have joined in undoing the wrongs of racism. Nevertheless, the silence that we met is not uncommon in many white churches across America, for example Emerson’s (1999) study showed that only 27 percent of white evangelicals agreed that discrimination plays a role in current racial inequalities.

We strongly believe all voices are needed at this time. If our white brothers and sisters are perhaps waiting for the right moment — this is indeed the moment. It’s a moment to rise beyond the moderateness Dr. King spoke against in his Letter from a Birmingham Jail when he wrote, “injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” We have before us a prophetic opportunity to speak with both imagination and urgency about suffering with those who suffer, and to seek changes to avoid further pain.

White churches can meet the silence with courage, compassion, and justice.

What is our response first and foremost? I believe Dr. King, who lived the politics of Christ, would encourage us to respond as the beloved community, children of God, to hold unswervingly to hope, and resist the apathy that corrodes the path of reconciliation.

We believe that this also means we cannot have church as usual this season. If we truly call ourselves brothers and sisters, at the very least we are called to compassion (to suffer with) and to empathy (to attempt to put ourselves in someone else’s place). In the wake of the Trayvon Martin tragedy Ms. Christena Cleveland poignantly expressed this call : “Privileged people of the cross seek out, stand with, and stick their necks out for people who have problems that are nothing like their own.” White churches can also participate in providing space and opportunity to grieve and work toward mending the brokenness that the death of young men of color have yielded in communities across America.

Here’s a sacred invitation, perhaps even a kairos moment, to make your voices heard in ways that speak to solidarity with suffering. We also encourage black, brown, Asian, and all faith communities that have internalized a fear and shame of being associated with negative stereotypes to break the wall of silence on addressing the killings of Michael Brown and Eric Garner. Let’s not be overdrawn by arguments on all sides of the media reports. Our desire is to focus on how the Gospel compels, and even draws us to human pain and brokenness together, regardless of whom we deem “right” or “wrong.”

We’d like to offer six ways you can courageously disrupt your church service by facing the brokenness together the next few Sundays:

1. Invocation & Prayer: Lead a prayer that honestly acknowledges the discomfort and fear that can come with addressing tragedies loaded with the pain and history of race.

2. Intercession : Pray for the police force, our local police precinct. Pray God’s protection and wisdom over the police commissioner.

3. Homily : Address the collective anger and grief of a people at the history of racial tension in our country and systems that no longer serve their communities.

4. Confess : Confess apathy — apathy about the possibility of healing and change, apathy about our mutual responsibility to one another as the family of Christ.

5. Communion: Set the table for communion with an acknowledgement that Jesus is familiar with suffering, and the table brings us into a fellowship of suffering and a unity that breaks the dividing walls of hostility.

6. Compassion is the word of the Day : Make it about the suffering of a community. Resist over intellectualization — don’t just make this about the facts of the case, but the dehumanization of all people involved.

Rev. José Humphreys is a faith organizer, and pastor of Metro Hope Covenant Church, a multi-ethnic church movement in East Harlem, NYC. José remains committed to shalom-making in NYC, through facilitating conversation across social, economic, cultural and theological boundaries. Dr. Mayra Lopez-Humphreys, part of the Emerging Voices Project, is a native New Yorker, professor, and pastor with more than 16 years of community engagement. She is also the associate pastor at Metro Hope Covenant Church, a multiethnic church that meets in Harlem’s historic National Black Theater.

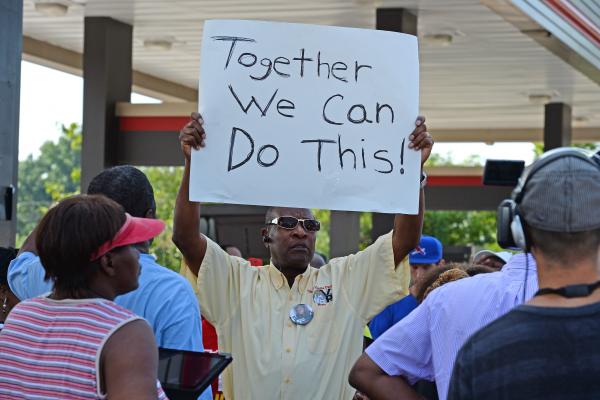

Image: Man holds sign at the site of QuickTrip after Police Chief Thomas Jackson release of the name of the officer that shot Michael Brown. R. Gino Santa Maria / Shutterstock.com

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!