A short walk from the Temple Mount, in the East Jerusalem neighborhood of Al Bustan, there’s a plan to replace dozens of Palestinian homes with a new tourist destination: a lush garden on the site where some say King Solomon built his royal gardens and wrote the book of Ecclesiastes.

Well, maybe there’s a plan. There definitely was one. But probably not now. At least, Ben Avrahami, who works with the spokesperson for the Municipality of Jerusalem, doesn’t think so.

“I'm not giving you, now, an official statement on behalf of the municipality. I'm not sure it's even right to cite me personally,” Avrahami told Sojourners during an on-the-record phone call last month. “Just telling you, as far as I know, there's no real plan to be implemented in this area."

Israel seized East Jerusalem from Jordan in 1967 and has effectively annexed it; the international community considers it occupied territory. Control of East Jerusalem has stymied peace negotiations for decades: For many Israelis, it is part of their eternal, undivided capital. For many Palestinians, it’s the capital of their future state.

Last month, a pending court ruling — since delayed — on orders to evict six Palestinian families in the East Jerusalem neighborhood of Sheikh Jarrah set off an 11-day war between Israel and Hamas, the militant Palestinian political group that controls the Gaza Strip. At least 230 Palestinians and 12 Israelis died in the fighting, including dozens of children.

Now, with a ceasefire in place and international attention focused on Sheikh Jarrah, some activists worry that authorities with the Jerusalem municipality may revive their plan to restore Solomon’s garden.

At the center of the controversy — maybe, depending on who you ask — is a settler group that has used archaeology and the Bible as weapons in the fight for East Jerusalem.

“In Jerusalem, there is thousands of years of history,” said Hadar Susskind, president and CEO of the anti-settlement group Americans for Peace Now. “And that thousands of years of history includes Jews, and it includes Muslims, and it includes Christians. That's an unequivocal fact.”

“But like any other facts, you can go through and you can decide exactly what moment you stop and what piece you highlight,” he added. “And, archeologically speaking, how deep you dig.”

‘No injunctions ... to protect us’

Avrahami’s claim that the city doesn’t have any plans for Al Bustan came as a surprise to Fakhri Abu Diab, who is head of the local residents’ committee.

“If he says they have no plans to develop The Bustan, it sounds as if he’s lying, because their plans are well known,” Abu Diab told Sojourners in a message sent through Israeli peace activist Angela Godfrey-Goldstein.

Abu Diab has been fighting against the plan to rebuild Solomon’s gardens since at least 2010, when former Jerusalem Mayor Nir Barkat proposed what he called the King’s Garden, or Gan Hamelech.

Barkat’s plan went on hold for a decade as the residents of Al Bustan put together their own proposal for the neighborhood and negotiated with city officials. Then, earlier this year, the city asked a local court to reactivate demolition orders for more than 70 unpermitted buildings, reigniting residents’ concerns.

Slowly, Abu Diab said, city officials are beginning to move in on Palestinian buildings in Al Bustan one by one.

“The city council hasn’t given any of us [residents] building permits, and there are no injunctions outstanding on the demolition orders, to protect us,” he said in late May. “Just four or five days ago, municipal inspectors came around handing out new demolition orders to replace those ones with expired dates.”

Since that time, Godfrey-Goldstein said, officials have been back in Al Bustan to hand out more demolition notices.

Avrahami downplayed the city’s request in March as “a recurring court debate” and said that there were no “proactive requests from the municipality to initiate it.” But he didn’t rule out the possibility that there could be evictions in Al Bustan in the future.

“If the court rules to evacuate, to demolish, whatever, when it comes to illegal housing units, we have to obey the law,” Avrahami said.

He did not reply when asked about Abu Diab’s response to his comments or the demolition orders.

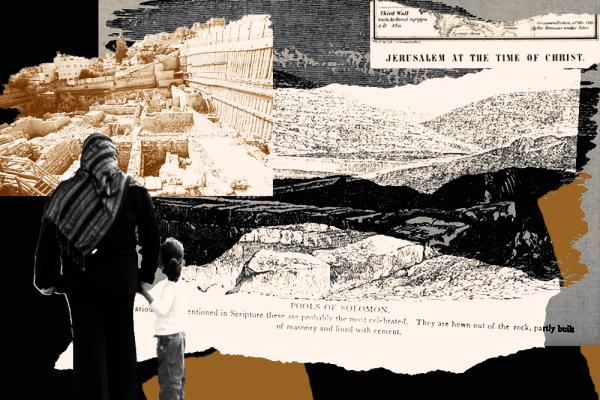

The Jerusalem of King David

On a slope next to Al Bustan sits the City of David, an active archaeological site and Bible park that has become a popular tourist destination. Visitors can see the ruins of what may have been King David’s palace, the Gihon Spring that supplied early Jerusalem with water, and the Pool of Siloam, where Jesus told a man to bathe while healing him in John 9:7.

The site is run by the Ir David Foundation, an Israeli settler group that has worked to cement the Jewish presence in East Jerusalem. For Ir David, which also goes by the Hebrew acronym Elad, its tourist sites, archaeological digs, and settlements go hand-in-hand.

Nowhere was that more on display than at Christians United for Israel’s 2019 summit in Washington, D.C. One of the largest pro-Israel groups in the United States, CUFI’s mission is to “unify Christians across all denominational and cultural boundaries in support of Israel.”

The group’s 2019 summit was a star-studded event even by Washington standards. Vice President Mike Pence spoke from a podium hung with his official seal. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu appeared live from Jerusalem. Rev. John Hagee, the evangelical minister and TV personality who founded CUFI in 2006, presided over the festivities.

Sandwiched in between the world leaders and power brokers was Ze'ev Orenstein, Ir David’s director of international affairs.

“We’re living in a time where, on the one hand, there’s unprecedented denial of the Jewish and Christian heritage in Jerusalem,” Orenstein said at the summit. “But at the same time, there is unprecedented archaeological discoveries that are affirming our shared heritage in Jerusalem.”

CUFI did not return multiple requests for comment on its relationship with Ir David, its stance on the status of East Jerusalem, or whether it has provided funding for the group.

The gardens of King Solomon

Almost as soon as Barkat, the former Jerusalem mayor, released his plan to rebuild Solomon’s gardens in Al Bustan in 2010, there were rumors that Ir David was involved.

Barkat denied those rumors in a 2010 interview with the Israeli newspaper Haaretz.

“I have been asked whether the Elad association is connected with the plan,” Barkat told Haaretz. “Unequivocally, no. The municipality is behind the project and the nature of the park is open to discussion. We will want to suit it to the millions of visitors who will want to come.”

Avrahami also said that the municipality and Ir David have not coordinated on the King’s Garden park.

In response to an inquiry from Sojourners, Ir David said that it is not part of the plan for the King’s Garden.

“The King's Garden is not a part of the City of David Project,” Yael Gershenfeld, a project manager for the City of David, said in an email.

Gershenfeld did not respond to a detailed list of questions about Ir David’s relationship to the King’s Garden proposal or respond to criticisms of the foundation’s work in East Jerusalem.

Still, many activists on the ground fear that the King’s Garden is an attempt by the city and Ir David to build a ring of Israeli- or settler-controlled parks, tourist centers, and archaeological sites around Jerusalem in order to choke off Palestinian claims to the land.

A map produced by the anti-settlement group Ir Amim shows what it calls a “settlement ring” around East Jerusalem that includes the planned King’s Garden park alongside the City of David and other sites operated by Ir David.

Together with the City of David, the King’s Garden would create “a contiguous Israeli touristic space” in Palestinian neighborhoods of East Jerusalem, according Amy Cohen, Ir Amim’s director of international relations and advocacy. Indeed, Haaretz reported in March that the King’s Garden would “blend in with” the City of David.

Ir David did not respond to Sojourners’ questions about that report.

“It only makes sense that [Ir David] would somehow be involved or promoting it, even if they're not necessarily involved, say, behind the scenes or institutionally at a state level,” Cohen said.

Ir David has been involved in other controversial projects to reshape East Jerusalem, including a planned cable car that would stop at its visitors center next to Al Bustan. Promoting the City of David is “the Zionist element of the project,” according to Barkat, the former Jerusalem mayor who first proposed the King’s Garden, and who is now a member of parliament from Netanyahu’s conservative Likud party.

“The City of David is the ultimate proof of our ownership of this land,” he told The New York Times for a 2019 story.

Evidence of the truth

Orenstein's appearance at the 2019 CUFI summit was hardly a one-off. He had spoken at CUFI’s leadership summit that January, and he shot a video for its virtual summit in 2020. CUFI’s website also carries regular updates on archaeological finds in the City of David, and the archaeological park features in many tours of Israel that CUFI organizes for clergy.

Ir David also celebrates visits by prominent U.S. politicians on its YouTube channel, from Democrats like former Massachusetts Gov. Deval Patrick and former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg to Republicans like former Housing and Urban Development Secretary Dr. Ben Carson and former Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker.

“I believe the Bible is true, but it’s also good for people to see actual evidence of the truth of the Bible,” former Sen. Rick Santorum (R-Pa.) said in one 2014 video. “Here, walking through the City of David, seeing this excavation, seeing the Bible come to life, is really quite remarkable.”

The archaeological discoveries at the City of David don’t just prove the Bible, according to Ir David — they prove Israel’s claims to sovereignty over East Jerusalem.

A week before the CUFI summit in Washington, the Trump administration sent U.S. Ambassador David Friedman, Middle East Envoy Jason Greenblatt, and Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.) to a ceremony put on by Ir David to celebrate the excavation of a Second Temple-era road that led Jewish pilgrims to the Temple Mount.

For David Be'eri, the founder of Ir David, the event had almost metaphysical significance.

“The Romans thought they had brought an end to Jewish life in Jerusalem,” he told the gathered dignitaries. “But today, nothing could be further from the truth. The Jewish people have returned to Zion and re-established our united capital here in Jerusalem.”

Friedman said that the road “brings truth and science to a debate that has been marred too long by myths.”

Digging up the Bible

At Ir David, the line between science and myth isn’t so clear. There’s some consensus among archaeologists, though it’s not unanimous, that the earliest settlement in Jerusalem was outside the current walls of the Old City, on the southeastern hill near where Al Bustan and the City of David’s archaeological digs now sit. It makes sense, according to Jodi Magness, a professor of religious studies at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, because that’s the location of the Gihon Spring — ancient Jerusalem’s only year-round source of fresh water.

Things get more complicated when it comes to showing that archaeological findings at the City of David prove that at least some parts of the Hebrew Bible are historically accurate, as Orenstein, Santorum, Greenblatt, and others have said.

In appearances on Fox News and videos on its YouTube page, Ir David likes to tie seals and other artifacts it has uncovered directly to obscure figures from the Hebrew Bible. Its marketing materials often feature Orenstein and others reading from the Tanakh while holding an artifact or standing at an archaeological site.

But not every scholar believes that the biblical account is an accurate view of history. The majority of scholars, who do believe that at least some of the Hebrew Bible is historically accurate, disagree on which sections are true to history.

Even dating a site like the City of David isn’t an exact science, according to Magness. Technologies like pottery dating and carbon dating provide a range, not a precise date.

“We can say that there are remains that date to the time when most scholars would agree David and Solomon lived, if they assume there was a David and Solomon,” Magness said. “But to then say, well, this proves the existence of a David or Solomon, or to prove that this shows that the biblical account is accurate — that's a whole other question.”

Then there’s the question that is at the core of Ir David’s work: whether ancient Israelite findings at the City of David prove the legitimacy of modern-day Israel’s current claims to East Jerusalem. Orenstein and others have said that Ir David’s discoveries prove the ancient Jewish connection to the land and belie claims by the Palestinian authority and the United Nations.

The problem, according to scholars who spoke with Sojourners, is that the Israelite findings in East Jerusalem are sandwiched in between material that pre-dates Israelite rule and material that comes after it.

“The undisputed historical fact is that Jerusalem has just been controlled by whoever was there and militarily powerful,” said Seth Sanders, a professor of religious studies at the University of California Davis.

“The entire history of the area before 1,000 [BCE], and the vast majority of the history after 586 [BCE], has been other people [ruling besides Israelites],” he added, “whether they were Babylonians, Persians, Hellenistic rulers, Romans, the Caliphates, Christian crusaders, and the Ottoman Empire.”

The archaeological record can help us figure out who was in power at what point in the past, experts say, but it can’t tell us who should be in power now.

Ir David has acknowledged the non-Jewish history of East Jerusalem on its website and at some of its conferences. But many of its public statements draw a straight line from King David’s reign over Jerusalem in about 1,000 BCE to Israel’s claims over East Jerusalem today.

The City of David may not be directly involved with the plan to rebuild Solomon’s gardens in Al Bustan, or to relocate Palestinian residents to do it. But there’s little doubt about its ultimate goal — and those of its supporters at groups like Christians United for Israel.

“The Jerusalem of today, the Jerusalem of 2,000 years ago, is one and the same,” Orenstein told CUFI in 2019. “The same people, the same faith. And its best days are yet to come.”

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!