The world would be different without Debbie Allen. For decades Allen has moved the culture through her art — from her award-winning role as Lydia Grant in the television show Fame to her time as the director of the sitcom A Different World and beyond. Allen, a former member of the President’s Committee on the Arts and Humanities, has directed episodes of The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air and Scandal, and she is now an executive producer of Grey’s Anatomy. But her present focus is on a project she called “probably the most important work that I’ve done in many years,” as reported by the Los Angeles Times.

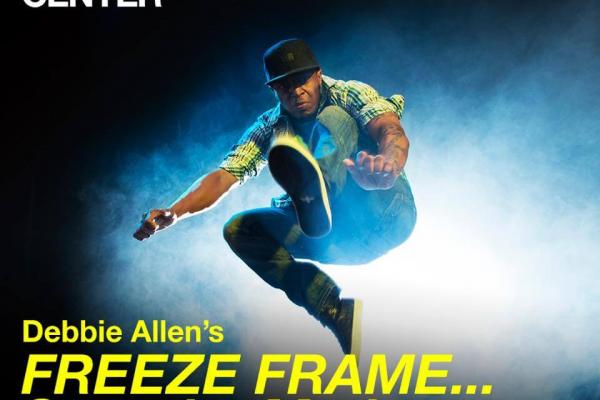

The project that Allen spoke of, titled Freeze Frame…Stop the Madness, is a work of theatre written, choreographed, and directed by Allen that combines cinema, dance, and music into a stage performance inspired by the issues of race and gun violence in America. Freeze Frame opened at the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C. on Oct. 27. On Oct. 24, Allen visited the Center for American Progress, in the nation’s capital, to discuss Freeze Frame’s creation and the impact she hopes the show will have on the U.S.

At a discussion on gun violence in America, hosted by the Center for American Progress, Debbie Allen was joined by Layla Zaidane, the managing director of the nonprofit Generation Progress; Jonathan Capehart, an opinion writer for the Washington Post; and three other esteemed panelists who know firsthand the pain of racism and gun violence.

Lucia McBath is the mother of Jordan Davis, a 17-year-old black teen who was shot and killed in Jacksonville, Fla., by Michael Dunn, in November 2012, because Dunn, a white male, thought that the music playing in Davis’ car was too loud. McBath is now the faith and community outreach leader for Everytown for Gun Safety, a nonprofit that aims to implement tougher gun control laws.

Jose Osuna is a former Los Angeles gang member who got involved with the organization Homeboy Industries — which provides jobs and free social services to gang-affiliated and previously incarcerated people — and is now Homeboy Industries’ director of external affairs, working alongside the organization’s founder, Fr. Greg Boyle.

DeJuan Patterson is a community activist and consultant for the BeMore Group and a victim of gun violence. In May 2016 he wrote an op-ed in the Baltimore Sun about the night he was robbed by gunpoint and shot and, afterward, in his bloody state, had another gun pointed in his face by the Baltimore police, who considered him a criminal before they deemed him a victim.

Alongside Allen, Zaidane, and Capehart, in front of an audience, McBath, Osuna, and Patterson shared their stories. And together the six people onstage discussed the nation’s collective pain.

When Capehart asked Allen how many times she has had to revise the narrative of Freeze Frame, in light of new national tragedies, Allen responded solemnly.

“Too many times,” she said. “I’m at a point now where I can’t keep up.” It’s her hope that her project Freeze Frame will help to stop the carnage.

“Art,” she said, “is, by design, here to reflect — be a lens through which the world can see itself and think … This dramatization will allow people to go in the theatre and feel, be inside, be inside the neighborhood and experience what happens.”

She continued:

“Take a look at this picture. Where do you see yourself in this picture? What can you do about it?”

Like the dialogue held at the Center for American Progress, Freeze Frame is multitudinous, in terms of the many perspectives and voices it contains. You don’t get a narrative with a single protagonist who can anchor you in the story. You get a black preacher’s son, a black woman who loves to dance, a mute Latino painter, a white police officer, and several other lives, several other stories.

And yet the drama of Freeze Frame seems to arise more so from systems (the culture of the police force, the general underlying and often blatant racism in the U.S., etc.) than from the intersection of those various lives. The young woman who loves to dance may not decide to further her study of the art form because her mother is on drugs. The police officer, who moved to Los Angeles for sunlight and warmth, has to decide whether to assimilate into the police department’s questionable policing tactics or risk not being able to provide for his family.

This is serious stuff and Allen handles it well. If some of the scenes of Freeze Frame are too sentimental and resemble an afterschool special, it’s because certain characters aren’t fleshed out, and they aren’t intended to be. Allen isn’t giving you the entirety of these characters’ lives, but rather snapshots, frames from a lengthy film reel. How else would she be able to paint for you, in an hour-and-a-half-long show, the vastness of the effect gun violence is having on our nation, in terms of the number of people it affects daily?

Fused with Freeze Frame’s storylines, the choreography of the show is fluid and often stunning. That may be expected from someone as highly regarded in the dance community as Allen, but nevertheless her excellent work, as well as the work of her dancers, deserves to be commended. Allen uses dance to give us another lens through which to view the topic of gun violence, the most prime example of this being when the police officers somewhat abandon their hostile nature to dance. Despite their guns — capable of great violence — being holstered to their sides, the officers move gracefully, like feathers taken by a light breeze. It’s simultaneously disarming and thought-provoking.

The biggest epiphany I had during the show came in the middle of a song called “Don’t Say No,” sung by young children about a giddy hope that the crush of one of the kids won’t say no to them wanting to be their sweetheart. It was while watching the talented children happily sing and dance that I realized how much we lose every day to gun violence. For who knows what creative potential is locked inside the victims who die too soon? Who knows the good they may have done for their families, their communities, our world?

It’s evident that Debbie Allen has thought about these questions seriously, and with every scene of Freeze Frame…Stop the Madness she encourages us to ponder them, too. Allen ignores the rhetoric surrounding the issue of gun violence and brings us to a deeper, mutual consideration of our wounds and our discord. It’s Allen’s hope that the production of Freeze Frame will travel across the country — it has already premiered in Los Angeles and Brisbane, Australia — and if the show goes on the road, many more people will be introduced to the show’s thoughtfulness. The effect that the show may end up having on the national conversation of gun violence could be significant.

If that happens, Debbie Allen will have once again moved our world with her work and her determination to change lives, and such a feat, although it would be extraordinary, wouldn’t be extraordinarily surprising. After all, making the world different is what Debbie Allen is good at. She’s been at it for a while. And Freeze Frame…Stop the Madness is evidence that she doesn’t plan on stopping anytime soon.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!