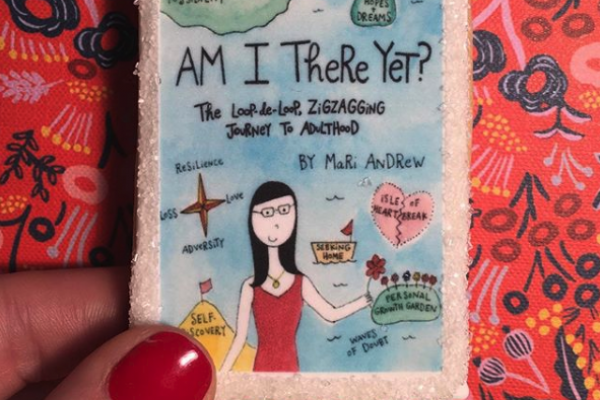

I met Mari Andrew a few years ago in Washington, D.C., when she became a contributor to a literary review I was co-running, The Wheelhouse Review. She soon became a friend. Since then, she's gone on to become a beloved illustrator and doodle-ist on Instagram. I recently met up with Mari to chat about her new book, Am I There Yet? The Loop-de-Loop, Zigzagging Journey to Adulthood — and to discuss faith, suffering, and the creative process. When the recording of our interview came back unintelligible, Mari was gracious enough to re-answer some of my questions, this time over WhatsApp.

This interview has been lightly edited for length.

Juliet Vedral, Sojourners: Tell me about Am I There Yet. What inspired you to write it?

Mari Andrew, Am I There Yet?: I have been writing this book for the past seven years. I really had to condense a lot of the feelings I was having in my 20s, which is what this book is about. It’s actually a sort of map of my 20s. It jumps around to different cities I’ve lived in and different cities I’ve visited and what each place — both physical place and each place in life — taught me about growing up.

I’d been writing essays about my growing up for a while, beginning when I was in my early 20s. And then when my father died when I was 28, I started kind of blasting through life. I had always wanted to write a book and I was like, “Why am I not doing this?”

I’ve also always been really drawn to illustration and really wanted to make a hobby out of it. And in the meantime, my Instagram kind of took off, so I incorporated a lot of my illustrations into this book, which was really fun. It wasn’t something I expected to do, but I like the way it turned out.

I like visual books myself, so writing a visual book was a really lovely experience.

Vedral: What has been the best part of getting your book published?

Andrew: Oh my goodness. It doesn’t feel at all how I thought it was going to feel, but I don’t know how I thought it was going to feel. It does feel so good when people tell me that they’re really comforted by it, because I love comforting things. I like feeling safe! It’s just amazing to feel like people are resonating with my work in that way. … The connections I’ve been making with people are just so fulfilling and special and make me really, really happy. So I think that’s been the best part. And also getting to write a second one, which I’m really excited about!

Vedral: You've experienced a great deal of suffering in the past few years: your father passing, a fire in your building, and getting Guillain-Barré Syndrome while traveling in Spain. Has your writing and illustrating helped you in getting through these situations?

Mari Andrew: I naturally process things externally, through creativity. I’ve always felt a need to write about things that happened to me. I think that’s just a personality type — it’s like I just have to write about them, I have to process them in some way.

Illustration is a new way that I’ve learned to process my emotions. It’s only a couple of years old for me. I find that it’s just as therapeutic and illuminating for me as writing. It really does help me get perspective.

When I was sick, I was paralyzed, temporarily, in my arms and legs, and I couldn’t write or draw, and that was really hard. I couldn’t do a lot of things that I normally loved to do, like take walks or just go to coffee shops. Just do normal life things. That was really, really difficult. There was this added difficulty of losing my identity, which was writing and drawing. So not being able to do those things really took a lot out of me. It was extremely depressing, and I still don’t really know how to deal with that.

Vedral: How did you hold on to hope when you weren't able to draw or create?

Andrew: I don’t think I did hold on to hope! It was really depressing. I don’t know how I would have handled it if it was a longer-term or permanent thing … I mean, I couldn’t even hold a pen. It was really, really, really challenging.

I love to be able to type and I love to be able to draw and journal with my hand. It’s really such a huge part of my life. To have that taken away from me so suddenly was devastating. I knew I would eventually get better but during the time, it wasn’t the best.

But I remember the first time I was able to journal, I had enough hand strength to write in my journal a few weeks when I was out of the hospital. It felt amazing. It felt like one of those videos of like, the cows who live in the slaughterhouses and someone rescues them and they get to walk on grass for the first time. And they’re leaping and dancing and, like, the happiest cows you’ve ever seen. That’s how I felt when I was able to journal again. It was like, “Oh this is what I’m made for; this is what I can do.”

So now I have a deep fear of losing my hand strength again, because it was so awful. But I do know that humans are extremely resilient, and somehow I would have gotten through it, even if I had permanently lost that ability.

Vedral: We've talked a lot about suffering and hope in the past, particularly about the problem of romanticizing suffering. Would you talk more about that?

Andrew: I think humans are just really, really uncomfortable with the idea that not everything hard has a purpose. I’m certainly uncomfortable about that.

It’s funny, when people ask me about my sickness, they always ask me what did I learn or how did I grow or what wisdom did I accumulate. Of course there are things that I learned, but I try to be really honest about that question. I don’t think that pain served any purpose. I didn’t learn anything. It sucked! I wish that I had been able to drink sangria instead. I wish that I had just had a happy life.

I think that in a lot of ways it made me worse. I think that it made me a lot more fearful, and I think it destroyed a romantic relationship of mine. It gave me depression for a few months. It made me distrust my body.

It’s very easy for people to say, “This will make you stronger,” or even, “You’re strong already, you’ll get through this.” But that’s just not really the whole story. And I think that it can be so easy to want to tie every story into a beautiful package, but that’s not the way that life works. I don't mean that I don’t think that you can go through some significant pain and get some perspective eventually, and see the ways it did positively contribute to my life. But I think that I could have gotten those lessons in a different way. I think I could have read a book about empathy and probably had the same experience of becoming more empathetic.

I really appreciated people who would just tell me, “Yeah this sucks, and I can’t believe you’re going through this and I’m here for you and here are some flowers.” That’s what really helped me.

Vedral: Though your book isn't about faith, there are elements of it that come through in some of your essays, like “Seasons.” Would you talk a bit about your faith? Has it changed as you've made your way through your 20s, and processed your grief?

Andrew: It’s definitely changed. Oh my gosh, where do I even begin?

I’ve always had a very, very rich inner spiritual life. Ever since I was a tiny little kid, adults would say that about me, like, “Oh, she’s going to be like a theologian or a philosopher.” I just always had that in me. Religion always made a lot of sense to me. I didn’t have a negative experience with it growing up.

When I was in college, I went to church constantly, loved it. It was a really huge part of my social life. And then after college I started examining it a little more, and realizing the way my experience of church didn’t quite align with my values anymore. I just didn’t feel very connected to it.

I’ve always been interested in arts, and I’m drawn to intelligent people and intellectual conversations and science and politics and these weren’t things that I really saw celebrated in the churches I was going to. I was very lucky to find the Episcopal Church, which I thought really celebrated all of that. I fell in love with it, so much so that I decided at a certain point I wanted to become a priest and I was going to work toward that. I loved communicating about my faith journey and I thought I had a gift for it.

In D.C., where I moved when I was 26 … I eventually found a Unitarian church and I really loved that, and it made me I realize, “Oh, I don’t have one type of faith, religion, spiritual practice that really works for me, I actually could have many of them.” I’m just a faithful person, in some way.

If you asked me what exactly I believed, I don’t know if I would have a great answer. … I do know that being a person of faith has inspired me to be a lot more compassionate and a lot more motivated politically and a lot more interested in people’s inner worlds and exploring my own inner world, which I’m writing about in my next book. And it really has helped me connect with people easily. So I’m really grateful for it.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!