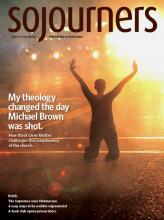

THE KILLING OF 18-year-old Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., last year and the events that followed sparked protests by the community in the St. Louis area asserting that black lives matter and ignited a discussion on race relations in the United States.

On the heels of non-indictments in the slaying of Brown and other black men, our nation focused its attention on the drastic inconsistencies inherent in our judicial system. To many observers, black lives had less standing in our nation than white lives.

Rodney King, Trayvon Martin, Mike Brown, Eric Garner, Tamir Rice, Walter Scott, and the churchgoers in Charleston, S.C., are part of a long list of black victims of violence. They are victims of an American narrative that devalues black souls, black lives, black bodies, and black minds. In response to these tragic events, particularly since the non-indictment of the police officers who killed Brown and Garner, many evangelicals have been calling for a biblical practice that is often absent in American Christianity—the call to lament.

On one level I am thrilled that evangelicals are discovering the importance of lament in dealing with racial injustice. However, I am concerned that the way lament is being used by some white evangelicals is a watered-down, weak lament that is no lament at all.

Lament is not simply feeling bad that Brown won’t be able to go to college. Lament is not simply feeling sad that Garner’s kids no longer have a father. Lament is not asserting your right to confront the police because, as a white person, you won’t be treated in the same way that a black protester may be treated. Lament is not the passive acceptance of tragedy. Lament is not weakly assenting to the status quo. Lament is not simply the expression of sorrow in order to assuage feelings of guilt and the burden of responsibility.

Read the Full Article