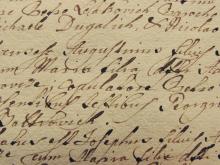

script

The exhibit is not intended as commentary on today’s politics, its organizers said. Work started on the project six years ago, before sharp rises in Islamophobic rhetoric and violence in the U.S. and Europe, and before Muslim immigration and culture became a flashpoint in American and European politics.

But the Smithsonian is not sorry for the timing, and hopes the exhibit can help quell fears of Islam and its followers.

WHEN I FIRST arrived in a western district of Georgia, on the shores of the Black Sea, in 2004, I met a group of young people walking along the muddy dirt road to school. They were walking slowly, linking arms and talking and laughing together. Like teenagers anywhere, the young people were happy to talk about their own lives: tensions with parents, boredom at school, friends, and anticipation of the future.

The girls that I spoke with also mentioned their fears of being abducted for marriage.

Surprisingly, in this modern era, the abduction of girls for marriage was still considered common and acceptable. In rural Georgia, if a young man fancied a young woman, he arranged with his friends to have her abducted as she walked home from school. If she was held overnight away from her home (and often raped), her chaste reputation was lost, and she had no choice but to leave school, marry him, and move in with his family. Honor demanded it.

In rural Georgian high schools, rumors flew about who was about to be kidnapped, or who was thinking of kidnapping someone. Boys thought it was romantic and a test of bravery and manhood. Almost all the boys we spoke with said they would help a friend abduct a girl if requested, and many said they felt pressured by their friends to abduct girls. It was seen as a way of proving yourself a man, a true Georgian man.

Most girls were afraid of being abducted, but some girls I spoke with had mixed feelings, wondering if they could manage to elope with their boyfriends using a traditional kidnapping story as the cover to overcome their parents’ disapproval.

THE FUNCTION of healthy religion and church is to provide individuals and society with a collective container that carries the objective truth of reality for individuals. The Great Truth is too grand and transcultural to be entrusted to the vagaries of individuals and epochs. Otherwise, society becomes a massive runway for unidentifiable flying objects—each claiming absolute validity and turning their subjectivity into the only sacred.

The ground for a common civilization and shared values is destroyed if our religious experience is basically unshareable or without coherent meaning. We end up where we are today: pluralism without purpose, individuation but no community.