baby boomers

FOR A SOCIETY already divided along race, class, and gender lines, the emerging divisions between young and old may become another crucial fracture—one that could sap our ability to make change. Or, if we understood it just a little differently, that fracture could heal in a way that strengthened our society.

You can see this division on many fronts. As the enormous and lucky Boomer generation has moved through our society, it has done a good deal of grabbing: Grabbing of money, as Boomers who grew up in an era of rising wages and cheap houses consolidated a relatively strong financial position. (You may not feel rich, but if you’re secure that looks awfully nice to Millennials struggling with college debt and living four to a sublet.) Grabbing of attention: For decades every company catered to the buying power of the generation, and even now its politicians are reluctant to surrender the stage.

It would be one thing if we Boomers had used the strong economic decades of our early lives to help make society stronger and more resilient. There’s much to be proud of: the civil rights and women’s movements, for instance. But on the whole, we’ll be the first generation to leave the world a worse place than we found it. Climate change, of course, is the perfect example: We’ve literally filled the atmosphere with so much carbon that we’re changing the operation of the planet. California has turned from golden idyll into smoke-choked danger zone; we’ve raised the oceans and melted the glaciers.

In the midst of so much death, how can we Christians celebrate Easter?

These questions can be paired with questions regarding our own sense of worship on that day. How much have we Christians replaced justice with worship, not taking one into serious relation with the other? Are we accustomed to worship in the total absence of justice?

You don’t need a doctoral degree to think higher education leads people away from organized religion. That’s been common wisdom for decades.

Now, a sociologist’s new generational study upends that thinking.

Today, it’s the least-educated members of Generation X—people born roughly between 1965 and 1980—who are “most likely to leave religion,” said Philip Schwadel, an associate professor of sociology at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln.

Millennials—Americans roughly between the ages 18 and 30—were not included in the study because, Schwadel said, it’s too soon to tell if they will settle on a religious identity.

Schwadel, whose study is published in the August edition of the journal Social Forces, found a clear historical shift.

“Americans born in the late 1920s and ‘30s who graduated from college were twice as likely to drop out of religion than people who didn’t graduate from college,” he said.

The postwar baby boomers proved to be “the last holdout of the church dropouts.” For boomers, “a college degree was still associated with a higher likelihood of leaving religion.”

However, for the generation born in the 1960s, there’s no difference between those who did and those who did not go to college in their likelihood of religious affiliation. Now, for America’s middle-aged adults who were born in the 1970s, “those without a college education are the most likely to drop out.”

National attention on a proposed Arizona law allowing business owners to deny service for religious reasons to gay people signals how attitudes on social issues have shifted dramatically in recent years.

Experts said such changes will accelerate on issues such as same-sex marriage, interracial marriage, legalization of marijuana, and childbearing among the unwed. Younger people are more liberal and less conventional, they said.

“We’re entering a period of massive social change,” said sociologist Daniel Lichter, of Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y. “This traditional pattern is reinforced by very large racial changes in America’s composition. The Baby Boomer generation — which is predominantly white and affluent and in some ways, conservative — in the next 20 [to] 30 years will be replaced by a younger population, and that population is going to be disproportionately minority.”

Baby boomers might not be that different from the Greatest Generation when it comes to religion. Like their parents, many boomers will attend religious services later in life. But unlike their parents, baby boomers are more likely to describe a deep, intense spiritual connection from a personal experience than a religious one from an institutional practice.

Many of them don’t know it yet, said a researcher at this week’s annual conference of the Gerontological Society of America in New Orleans, but growing old, regardless of what generation you belong to, brings on dramatic changes that can propel people to seek new meaning in religious services.

Vern Bengtson is the author of the recently published Families and Faith with co-authors Susan Harris and Norella Putney. He based his findings and predictions on a 35-year longitudinal study of 350 Southern California families and interviews with a subset of 156 families. The study’s scope spanned six generations from 1909 to 1988. The conversations explored spirituality, religious beliefs, intensities, and practices.

As baby boomers start clicking the senior citizen box on travel fares, I want to say a word to my generation and to the one that preceded us.

It is time for us to get out of the way.

I don't mean easing into wheelchairs. For the most part, we're way too healthy and energetic for that. I mean the harder work of relinquishing control.

I see that need most clearly in religious institutions, where I work. But I see it elsewhere, too, from taxpayer "revolts" led by seniors against today's schoolchildren to culture wars that we won't let die.

Psalm 78:1-8

Hear my teaching, O my people;

incline your ears to the words of my mouth.

I will open my mouth in a parable;

I will declare the mysteries of ancient times.

That which we have heard and known,

and what our forebears have told us,

we will not hide from their children.

We will recount to generations to come

the praiseworthy deeds and the power of the Lord,

and the wonderful works he has done.

He gave his decrees to Jacob

and established a law for Israel,

which he commanded them to teach their children;

That the generations to come might know,

and the children yet unborn;

that they in their turn might tell it to their children;

So that they might put their trust in God,

and not forget the deeds of God,

but keep his commandments;

And not be like their forebears,

a stubborn and rebellious generation,

a generation whose heart was not steadfast,

and whose spirit was not faithful to God.

I'm pondering the first few lines of this Psalm. They strike me as remarkably different from much of what we're saying these days about generations and faithfulness. It is, it seems, always the younger generations who fail us, who are stubborn and do not recognize the gifts of God. Every so often someone will throw the Baby Boomers (I mean, that's fun, right?) under the bus, but the majority of our attention has been on the future generations or those who are simply young now. We who analyze religious trends are practitioners of religious prognostication.

Comparing today with yesterday is a popular yet pointless pastime.

For one thing, we rarely remember yesterday accurately. More to the point, yesterday was so, well, yesterday — different context, different players, different period in our lives, different numbers, different stages in science, commerce, and communications.

Seeking to restore the 1950s — grafting 1950s values, lifestyles, cultural politics, educational, and religious institutions — onto 2012 is nonsense. It sounds appealing, but it is delusional.

That world didn't disappear because someone stole it and now we need to get it back. It disappeared because the nation doubled in size, white people fled racial integration in city schools, and women entered the workforce en masse. It disappeared because factory jobs proliferated and then vanished, prosperity came and went, schools soared and then soured, the rich demanded far more than their fair share, overseas competitors arose, and medical advances lengthened life spans.

The comparison worth making isn't between today and yesterday. It is between today and what could be. That comparison is truly distressing, which might explain why we don't make it.

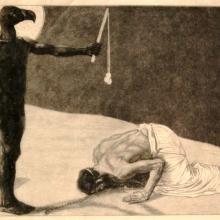

Der Mammon und sein Sklave. Holzstich, 1896 via Wiki Commons, http://bit.ly/zom5Df.

Tuesday's New York Times carried a thought-provoking op-ed by David Brooks called "The Materialist Fallacy." I recommend that you read it: it's only 764 words long. Brooks argues that "in the half-century between 1962 and the present, America has become more prosperous, peaceful and fair, but the social fabric has deteriorated." This is not just because of job loss (the liberal explanation) or government intrusiveness (the libertarian explanation) or "the abandonment of traditional bourgeois norms" (the neo-conservative explanation).

It has more to do with declining social context and social capital, says Brooks, who never met a financial capitalist he didn't like. He really likes Charles Murray's new book, however: Coming Apart: The State of White America, 1960-2010. (If you're not up for the 416-page book, you might want to read Brooks's January 30 column in praise of it.) Both authors worry about nefarious social forces that are driving a wedge between rich and poor, productive and non-productive, law-abiding and outlaws.

Brooks is partly right, and so are his critics. Yes, there's a rip in our social fabric. Yes, it is caused or made worse by job loss, ill-advised government programs, and shifting (or abandoned) values. Yes, it diminishes social capital and impoverishes social context. But also, Mr Brooks, and perhaps fundamentally, our decaying social fabric is the direct result of our enthusiastic worship of Mammon--the love of money that is the root of all evil (1 Timothy 6:10).

I don't need to remind anybody about rapacious financiers, bloated CEOs, unscrupulous lobbyists, and corrupt politicians. But there were plenty of those in the 1890s and the 1920s, and, as Brooks points out, the social fabric still stayed more or less intact back then. Even two World Wars and a Great Depression didn't unravel it. People still finished school, still got jobs, and still got married before having children, if not always before getting pregnant. Why did things start to break down in the 60s?