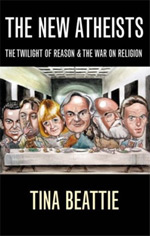

Following is a continuation of Becky Garrison's e-mail exchange with Tina Beattie, author of

Following is a continuation of Becky Garrison's e-mail exchange with Tina Beattie, author of

Read the Full Article

To continue reading this article — and get full access to all our magazine content — subscribe now for as little as $4.95. Your subscription helps sustain our nonprofit journalism and allows us to pay authors for their terrific work! Thank you for your support.

Already a subscriber?

Login