Dec 6, 2007

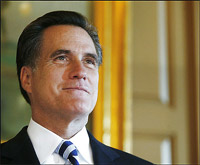

In what may be the defining moment of his campaign, Mitt Romney, the former governor of Massachusetts and a Mormon, addressed the issue of faith and its bearing on his pursuit of the presidency. Pundits inevitably compared Romney's speech in College Station, Texas, with the speech that John F. Kennedy gave just down the road at the Rice Hotel, Houston, on September 12, 1960.

In what may be the defining moment of his campaign, Mitt Romney, the former governor of Massachusetts and a Mormon, addressed the issue of faith and its bearing on his pursuit of the presidency. Pundits inevitably compared Romney's speech in College Station, Texas, with the speech that John F. Kennedy gave just down the road at the Rice Hotel, Houston, on September 12, 1960.

The parallels [...]

Read the Full Article

Already a subscriber? Login