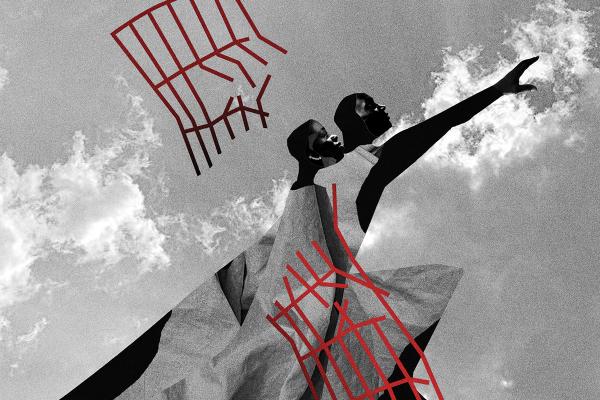

BLACK LIVES MATTER. In the years since 17-year-old Trayvon Martin was murdered in his hoodie carrying Skittles, we have learned why this phrase is not simply a consequence of all lives mattering. The world systematically devalues Black life, turns Black life into death-bound life, and it is our task — as justice seekers and as Christians — to embrace Black resurrection.

Politically that makes sense, but what does it mean theologically? Surely Christianity proclaims that all might be saved, independent of skin color. A half-century ago, James Cone and fellow Black theologians embraced this theological challenge head-on. They charged that the possibility of life after death for any individual is inextricably linked to the struggle against the death-dealing forces of white supremacy. How might we fill out this insight today, with Black Power slogans themselves finding new life and new form as activists embrace Black joy, Black excellence, Black rage, Black love, and Black dignity?

In a definition that has rapidly gained traction in activist circles, Black prison abolitionist and scholar Ruth Wilson Gilmore defines racism as “the state-sanctioned or extralegal production and exploitation of group-differentiated vulnerability to premature death.” Black studies scholars have refined and deepened this claim, arguing that anti-Black racism names a system of laws, institutions, feelings, and even forms of seeing and thinking that make Black life particularly vulnerable to premature death. Slavery may have ended in the 19th century, but many of the structures and habits that made slavery possible, that made it plausible for Black human beings to be treated as less than human, persist, and those structures and habits function by making Black life precarious. One false move, and the police officer or prison guard or neighbor or privileged “Karen” may invoke the violent power of whiteness to put an early end to Black life.

Read the Full Article