I WAS SITTING in a large auditorium full of market researchers. A speaker suggested that, by selling wrinkle cream, we were helping to make the world a better place because women would feel better about themselves. I looked around the room, thinking, “Is everyone buying into this? Do people really think this is true, or do they see that it’s just a corporate pep talk?”

I had worked in the world of international market research for nearly 10 years. Though there were a few moments like this one when something just didn’t feel right, in many ways I still didn’t see the issues I see so clearly now — marketing techniques are the air we breathe.

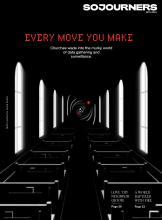

I eventually left my work in marketing to pursue a master’s in social justice and a doctorate in theological ethics. I began to investigate how marketing practices negatively impact how we live as human beings and how we think about marketing in the church. In contemporary society, we tend to view marketing techniques as neutral tools that can be applied in different contexts — whether for businesses, nonprofit fundraising, or church communication. But can we adapt tools that have been developed in the context of capitalistic profit maximization to the mission of the church? Are there fundamental differences in how the church views and relates to human beings?

I had worked in the world of international market research for nearly 10 years. Though there were a few moments like this one when something just didn’t feel right, in many ways I still didn’t see the issues I see so clearly now—marketing techniques are the air we breathe.

Read the Full Article